Whitechapel in East London is a place of constant change; an endless reinvention, reputed to be located at the furthest an immigrant family could walk in a day carrying their scant belongings from the docks bordering the Thames to the east. The closest they could camp to the riches of The City lying beyond its gates. The histories of the people who lived and worked there were laid down repeatedly, buried and rediscovered with passing generations. Below the surface are centuries of the detritus of life, abandoned objects, layered together like fossils, slowly returning to the earth, some never to be found again.

It’s the smaller mass-produced objects, the products of industry that disappear so quickly – the utilitarian objects of an age that no longer serve a purpose in an ever changing world. They melt away from sight, some swept away, some

buried, some rotting in the ground. These are the artifacts we want to forget, and for many of these objects and places there remains no interest, no beauty and no afterlife. Repurposing had not found its day in the late 70s.

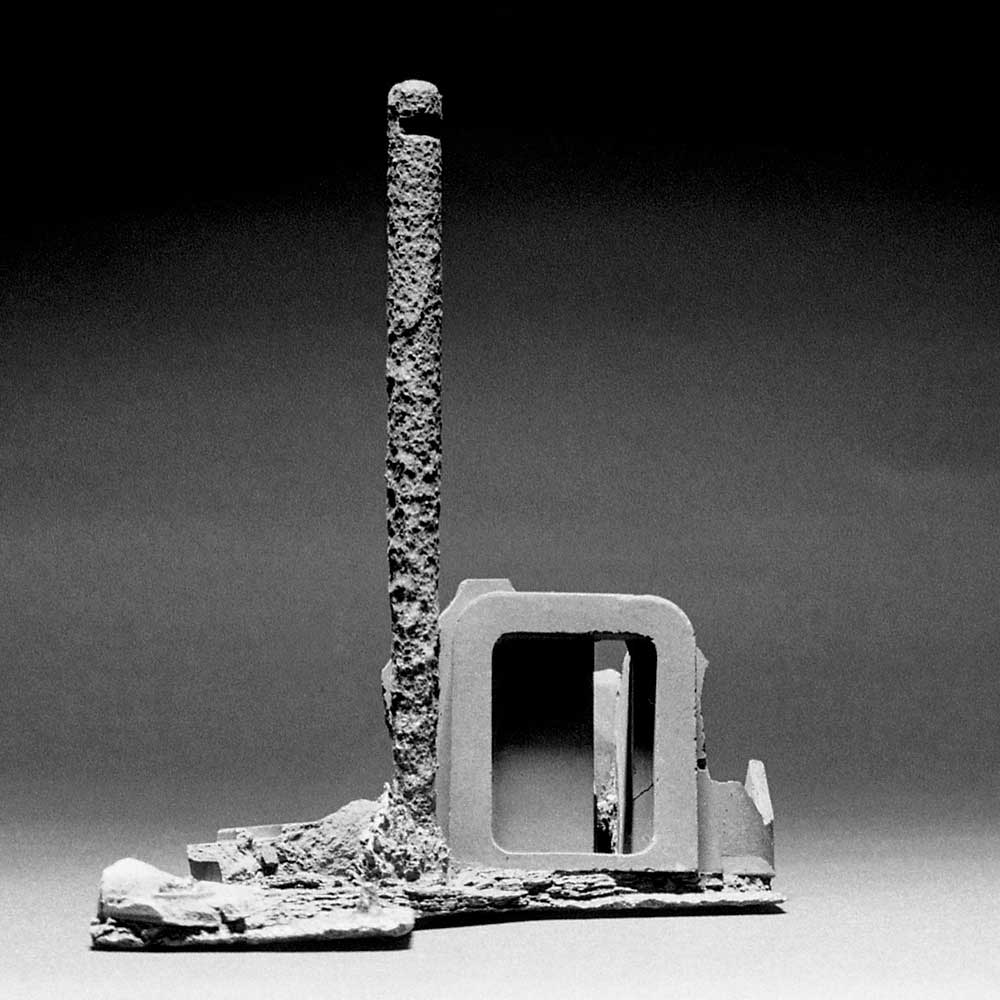

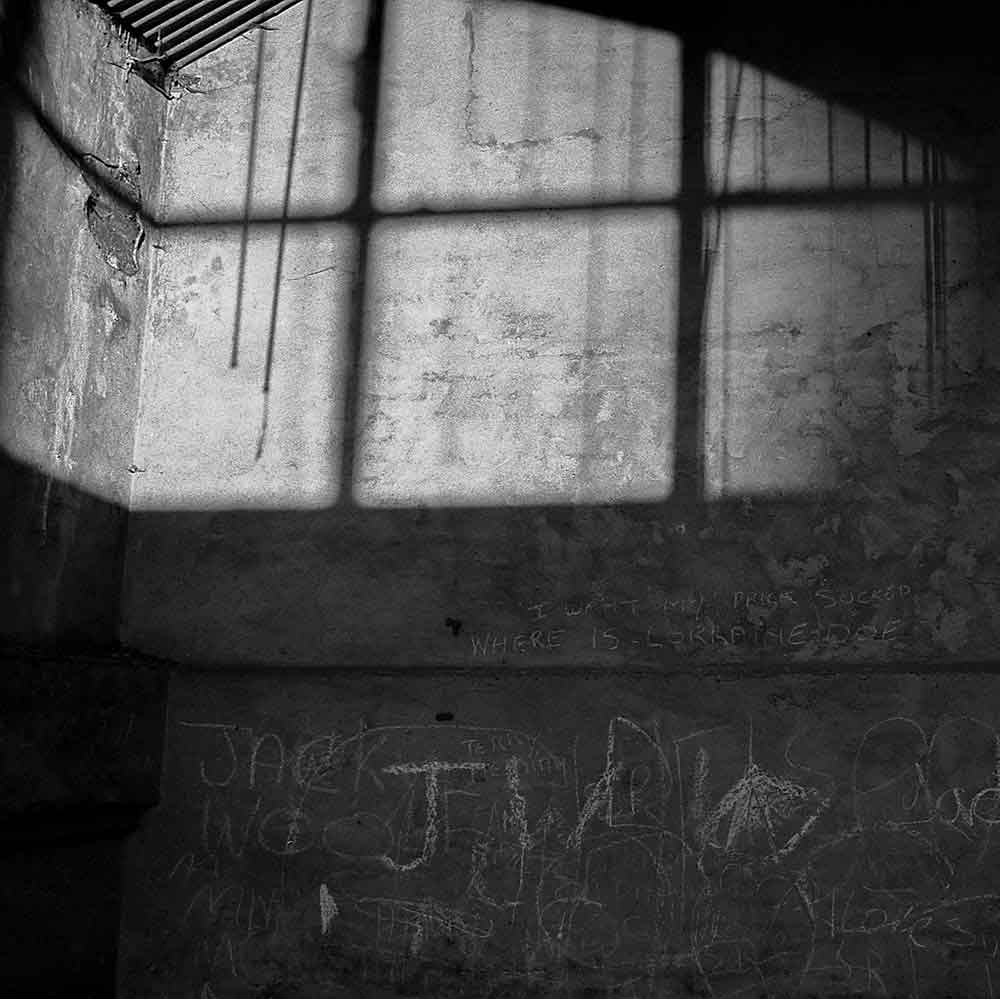

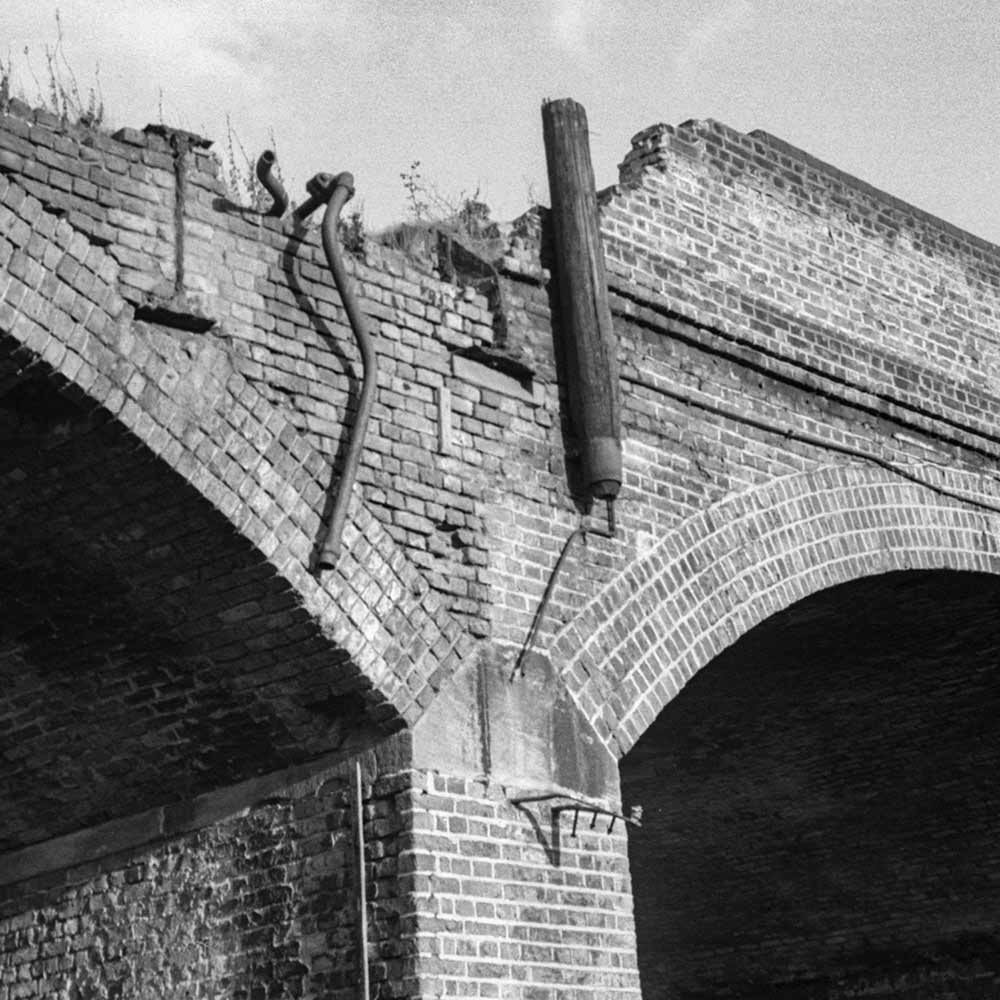

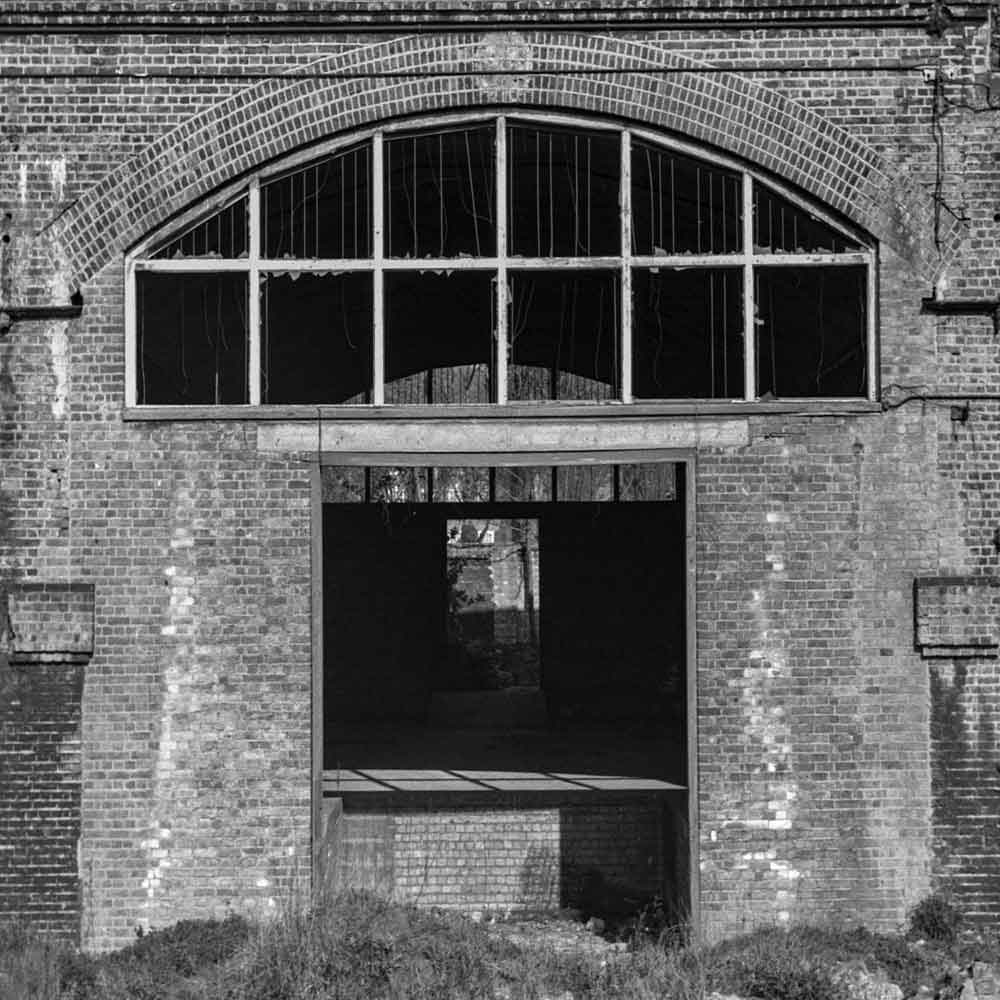

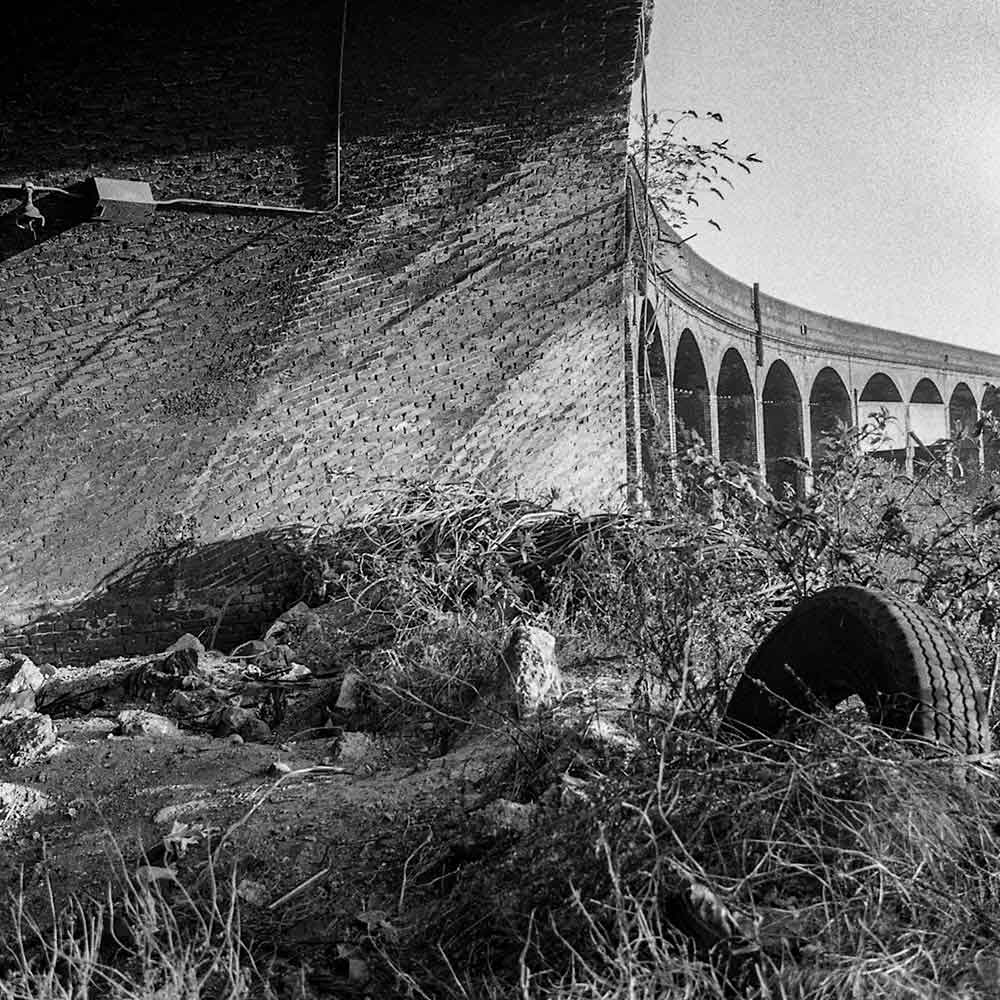

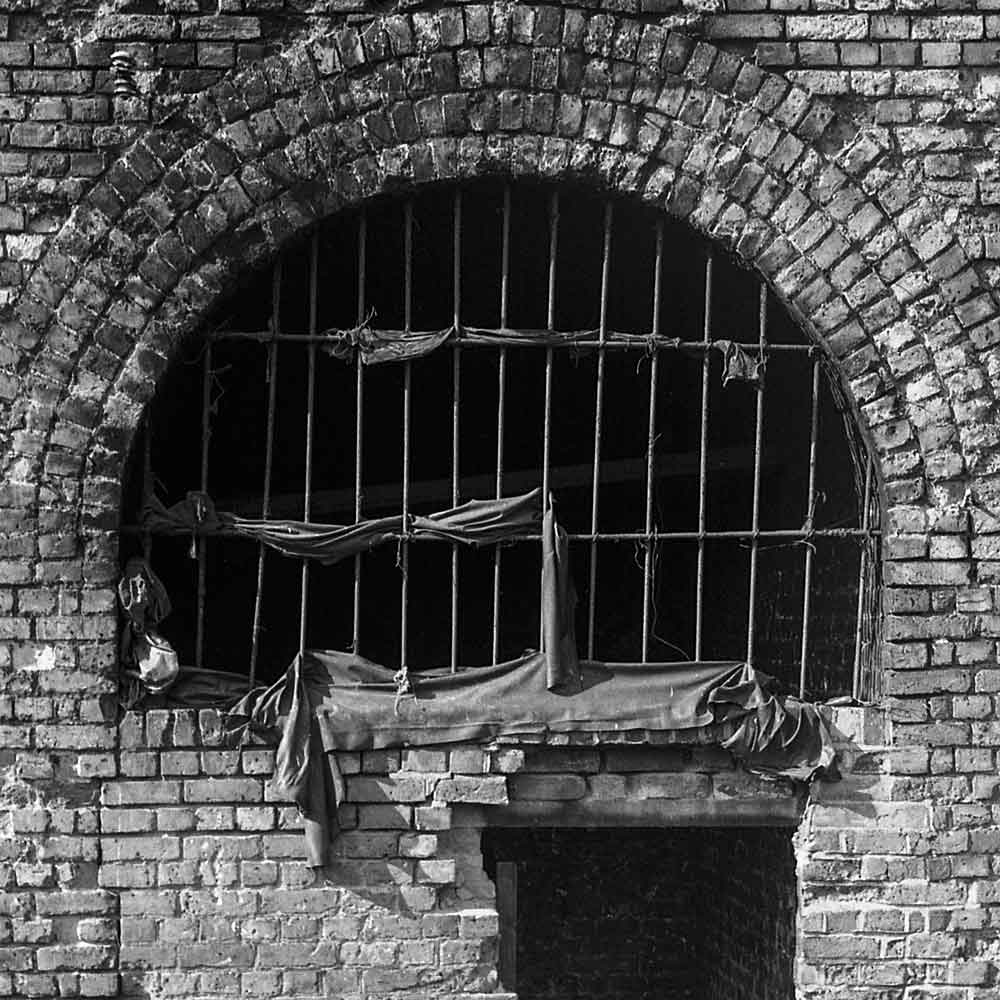

I came to know one of these places when living near Whitechapel Station throughout the 1970s. During my time there, I photographed the abandoned land behind the station, littered with disused coal sheds and the arches of the railway spur curving away from Shoreditch and Spitalfields.

So how did I come to find such beauty in this coal-dusted, dying place frequented only by those who had no other place to go? Training as a silversmith and jeweller at Sir John Cass School of Art, I worked part time in the college holidays in engineering

shops learning the skills of pattern making; immersed in a world of repetitive machine work producing swivel bushes for Citroen car headlights, or perhaps small but essential parts for Rolls-Royce RB211 engines in the small machine shops of Leicester, my home town.

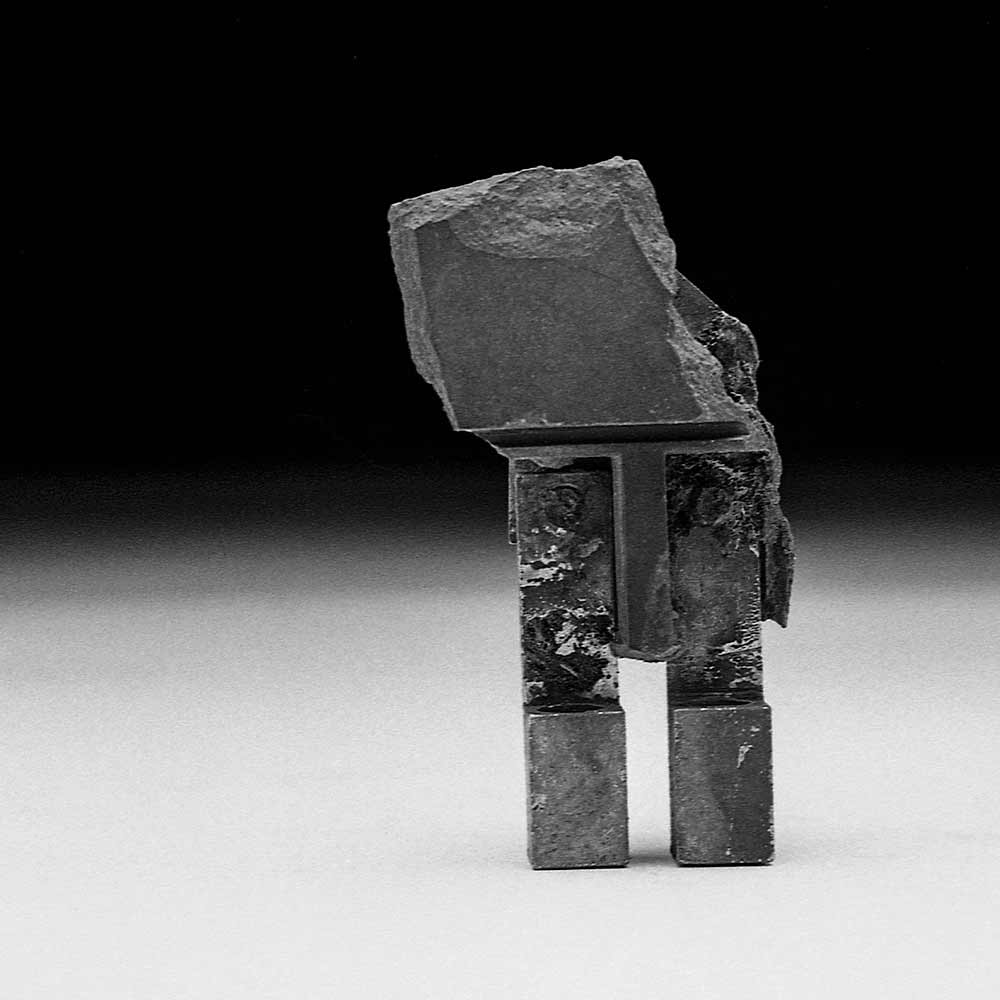

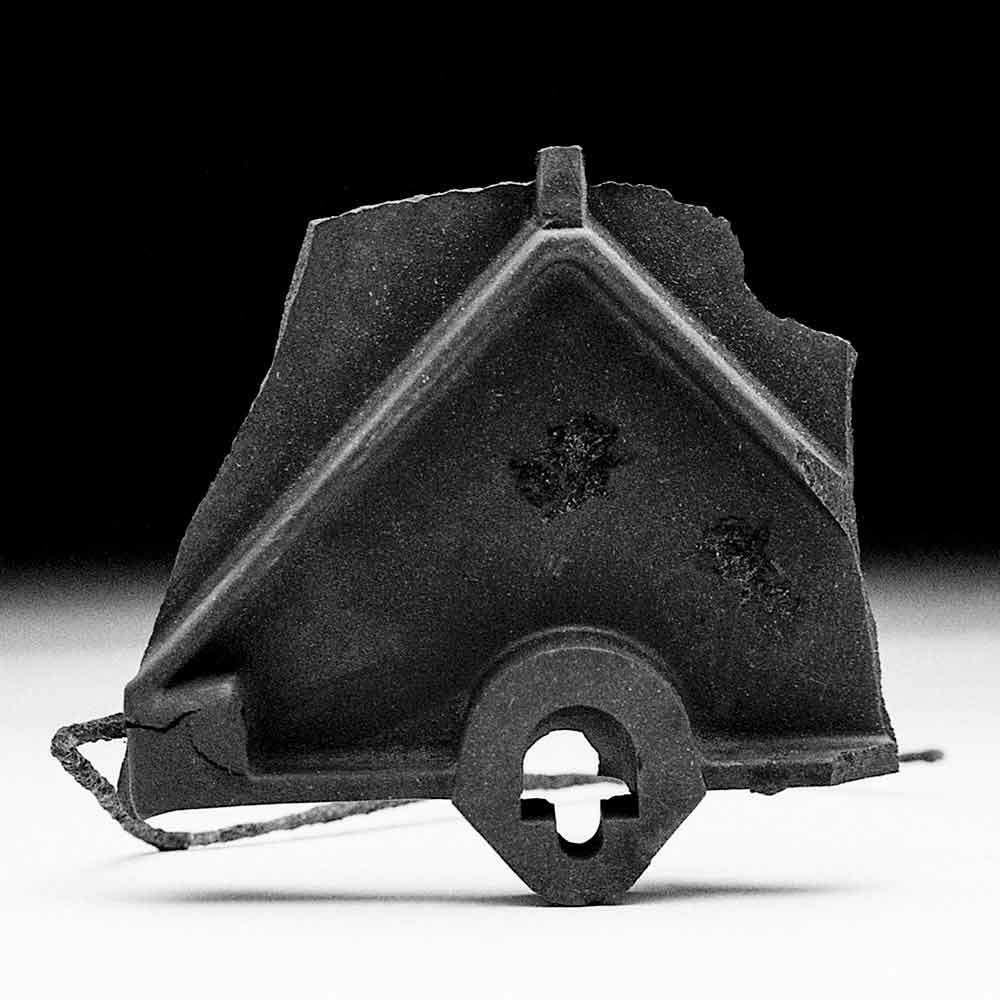

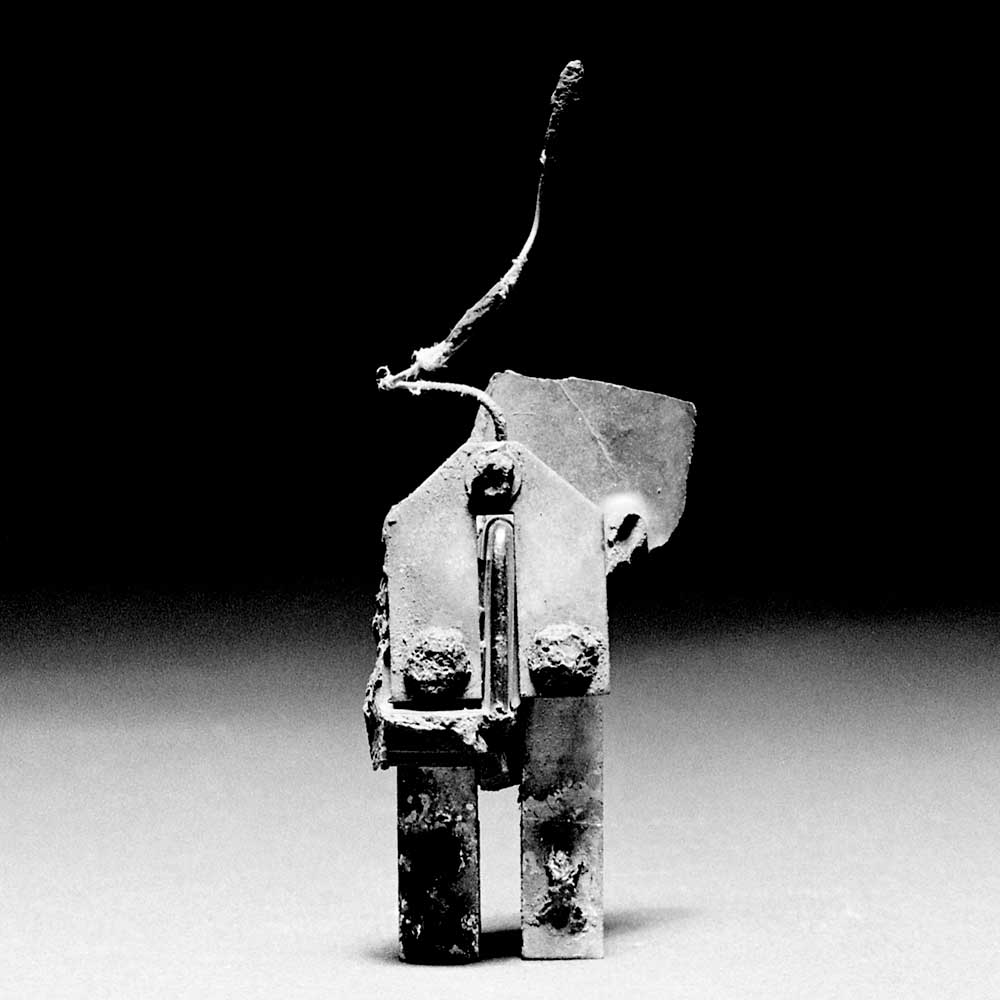

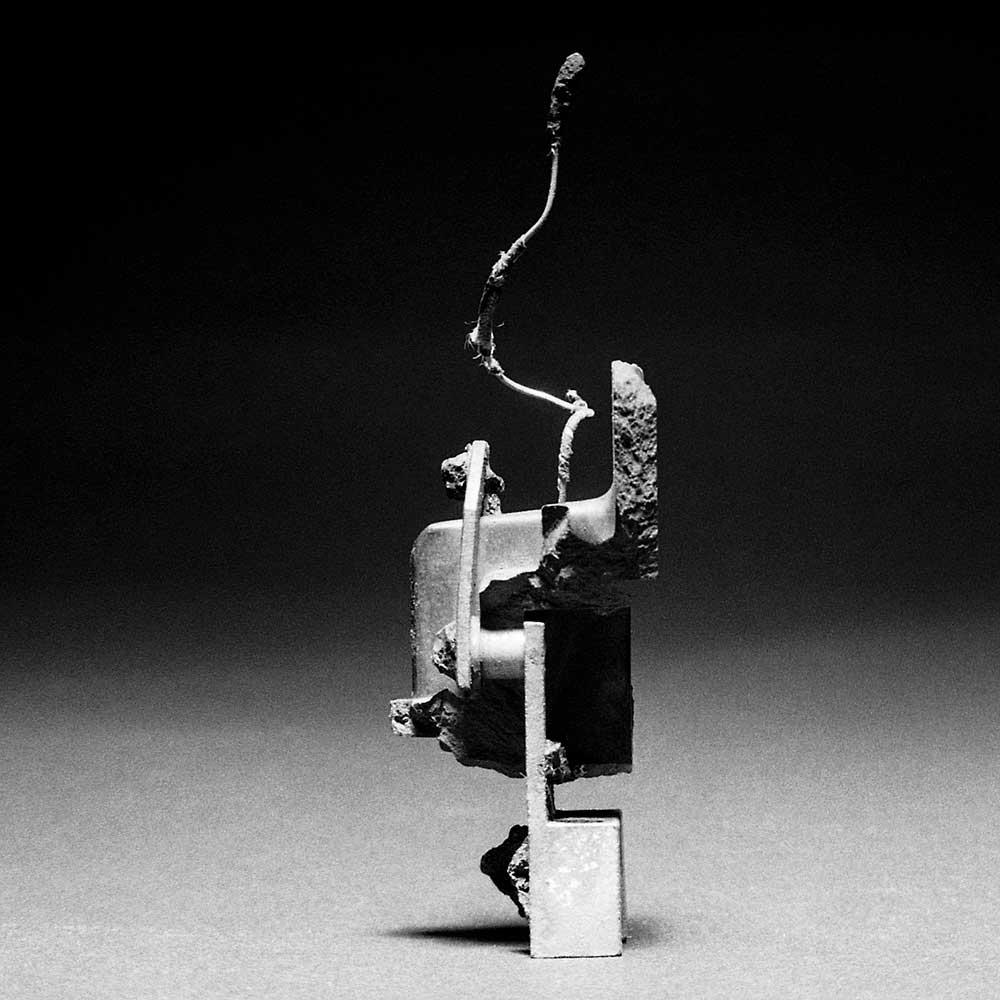

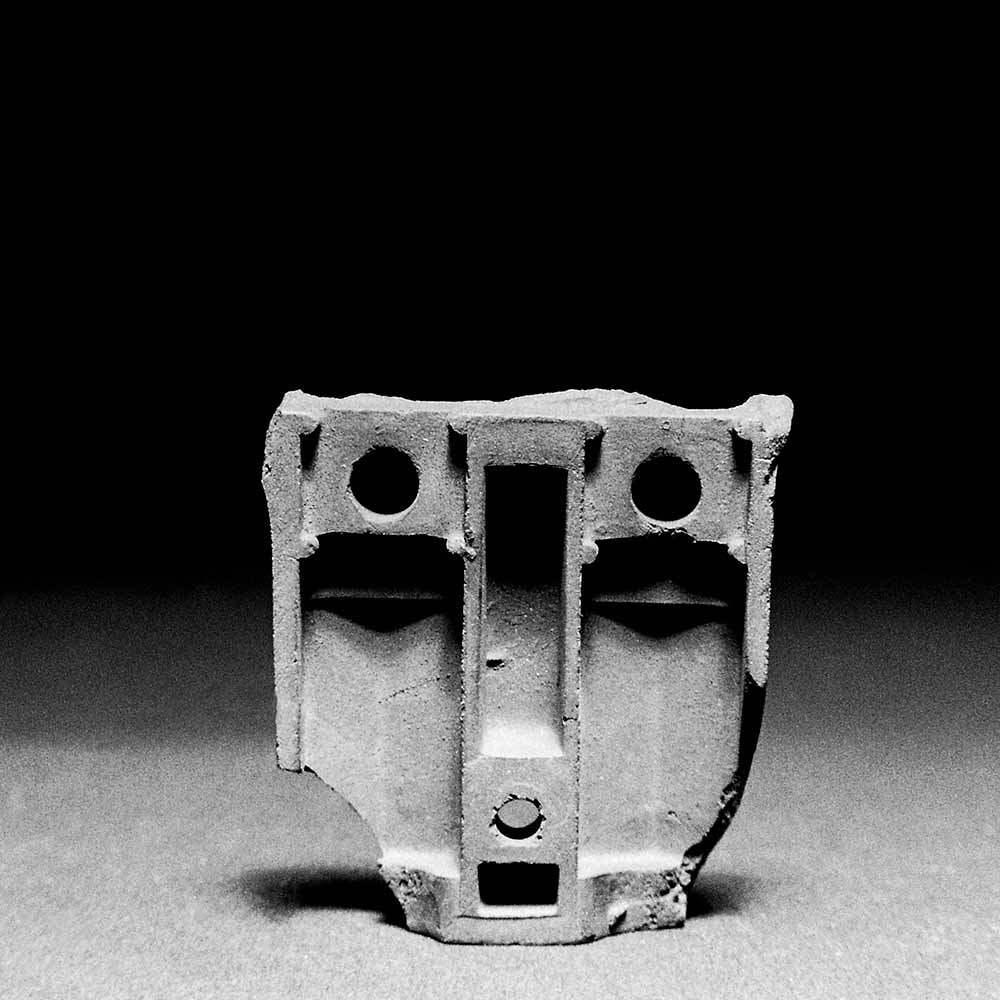

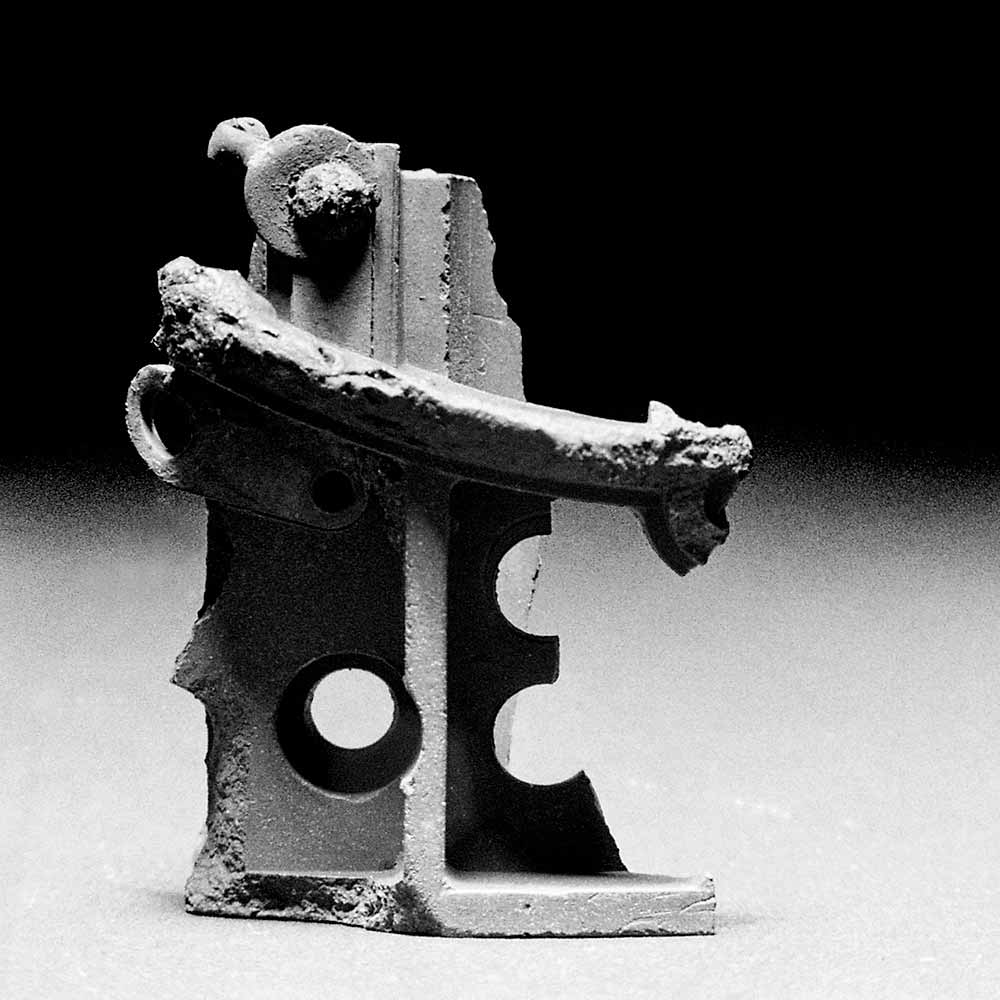

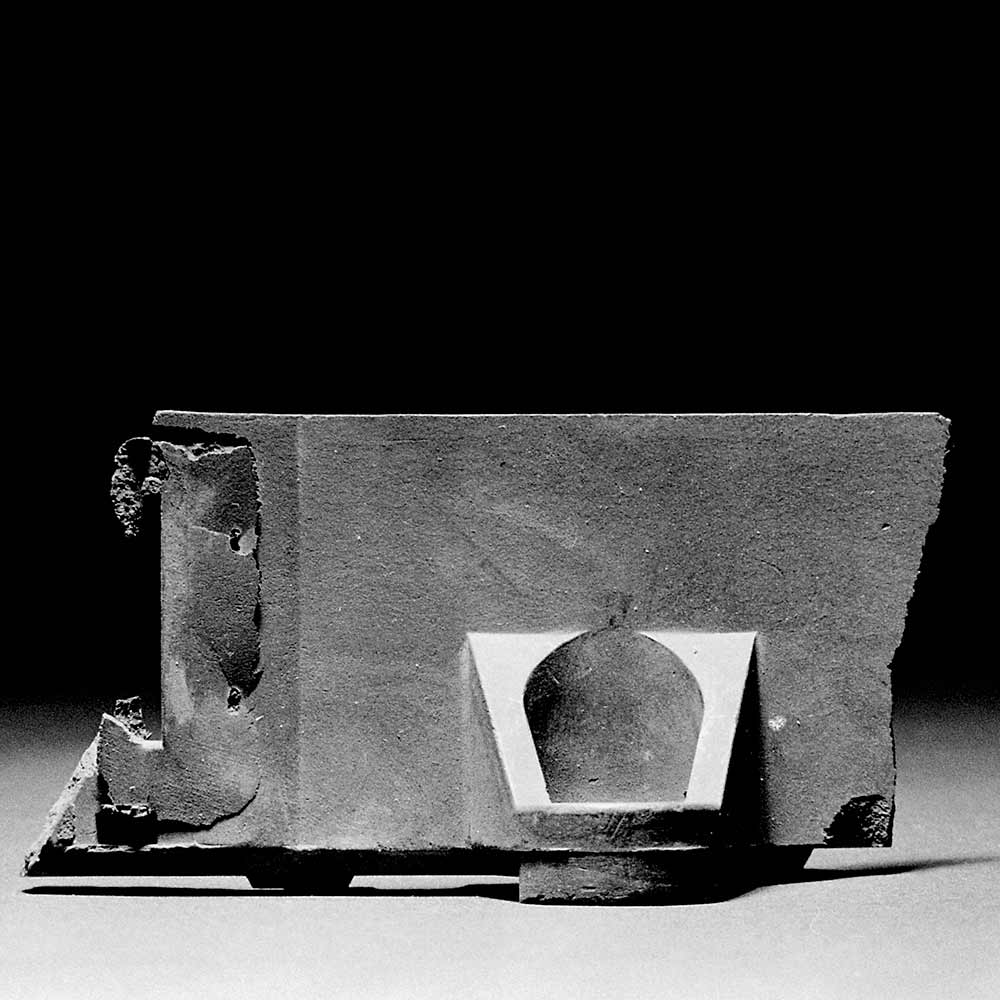

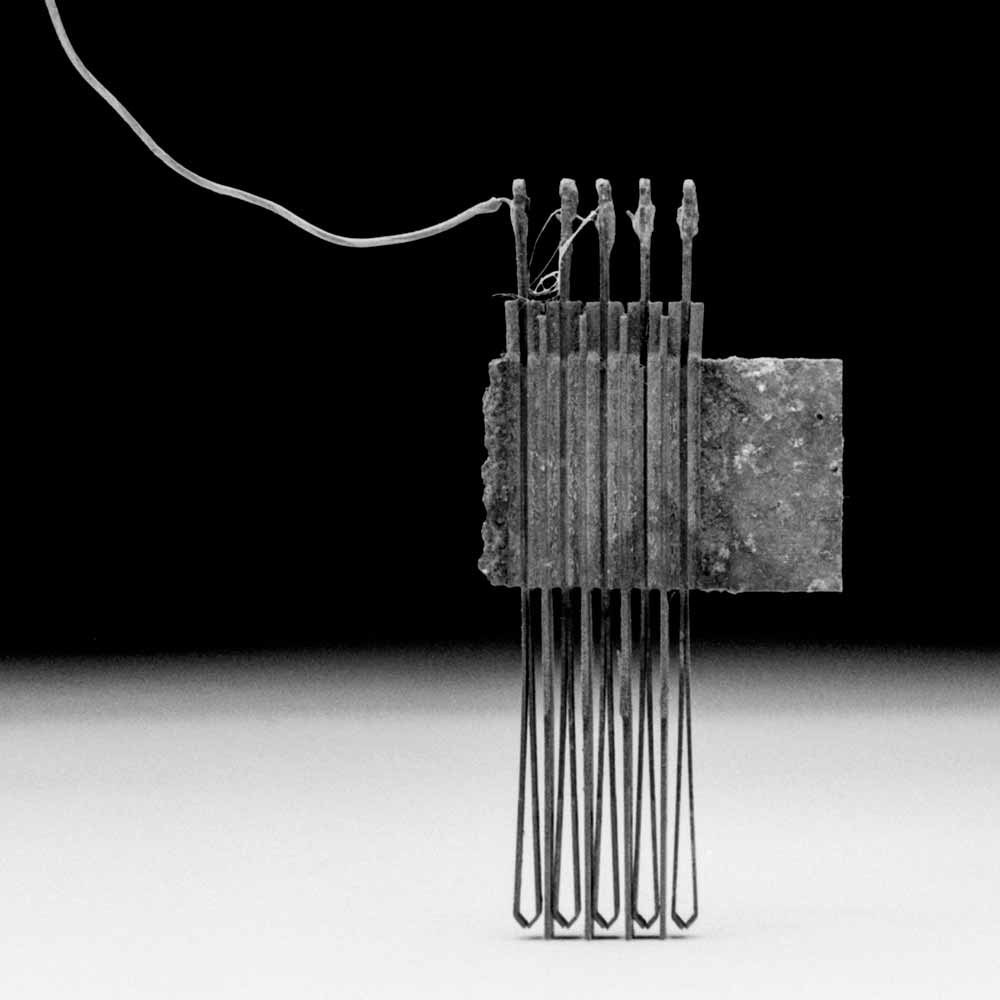

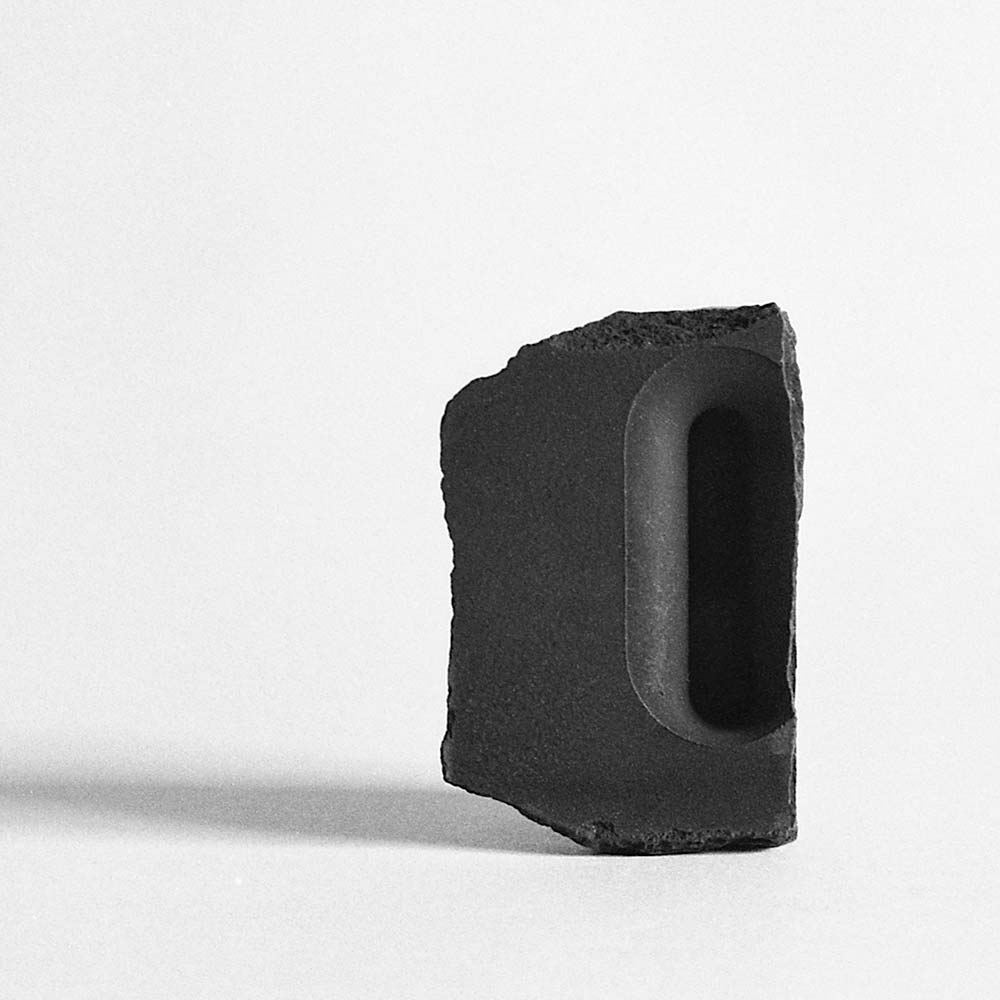

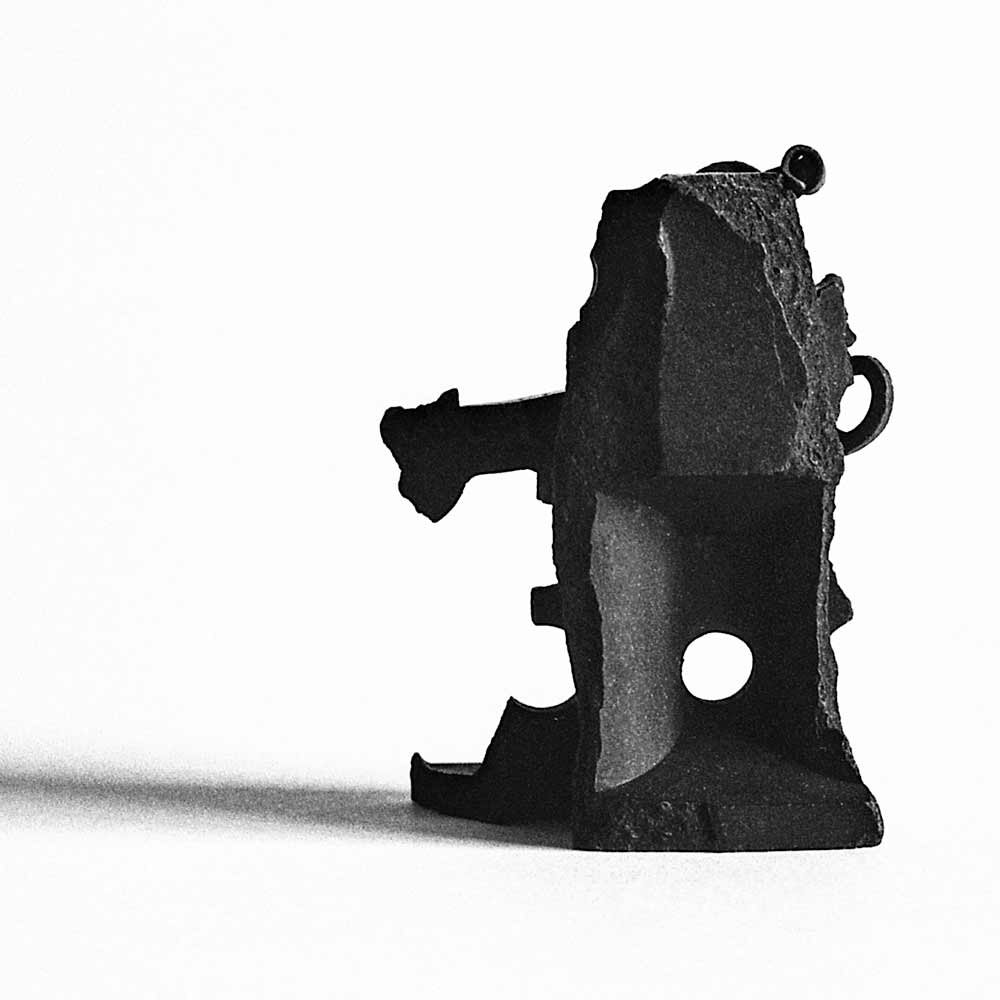

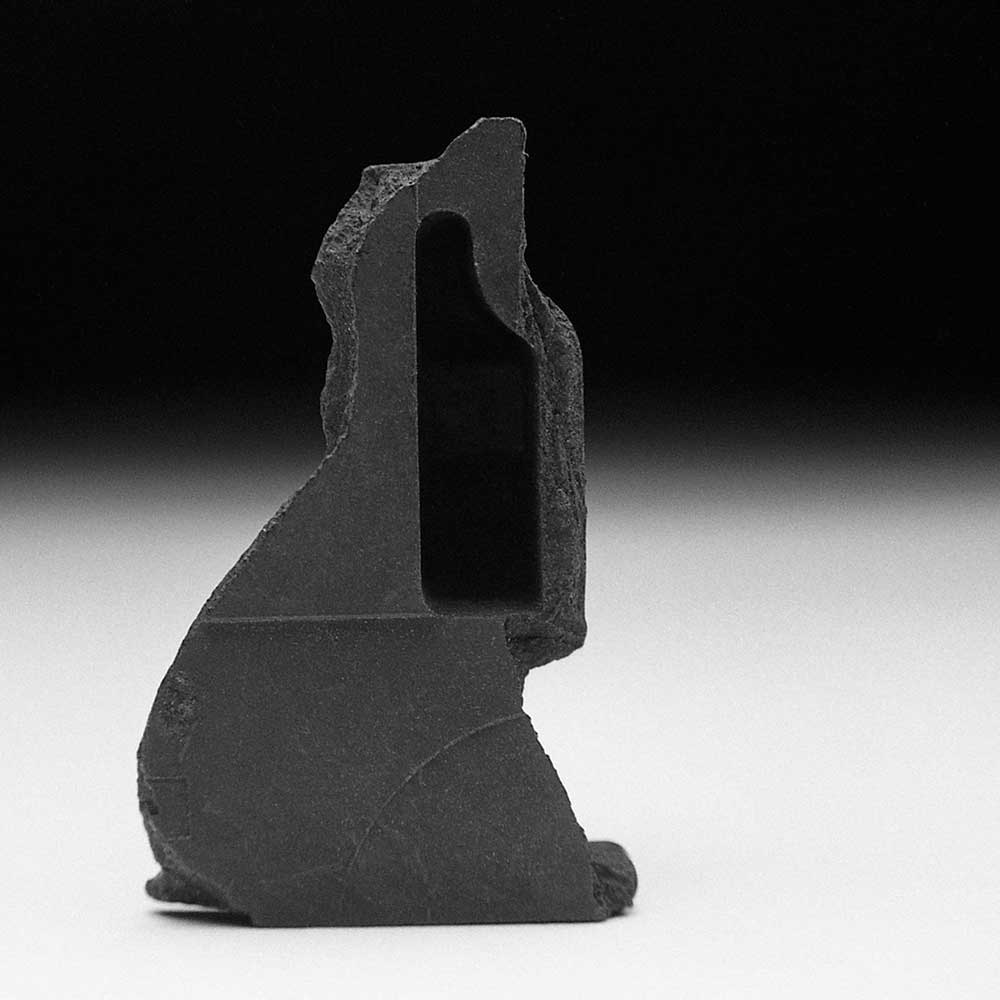

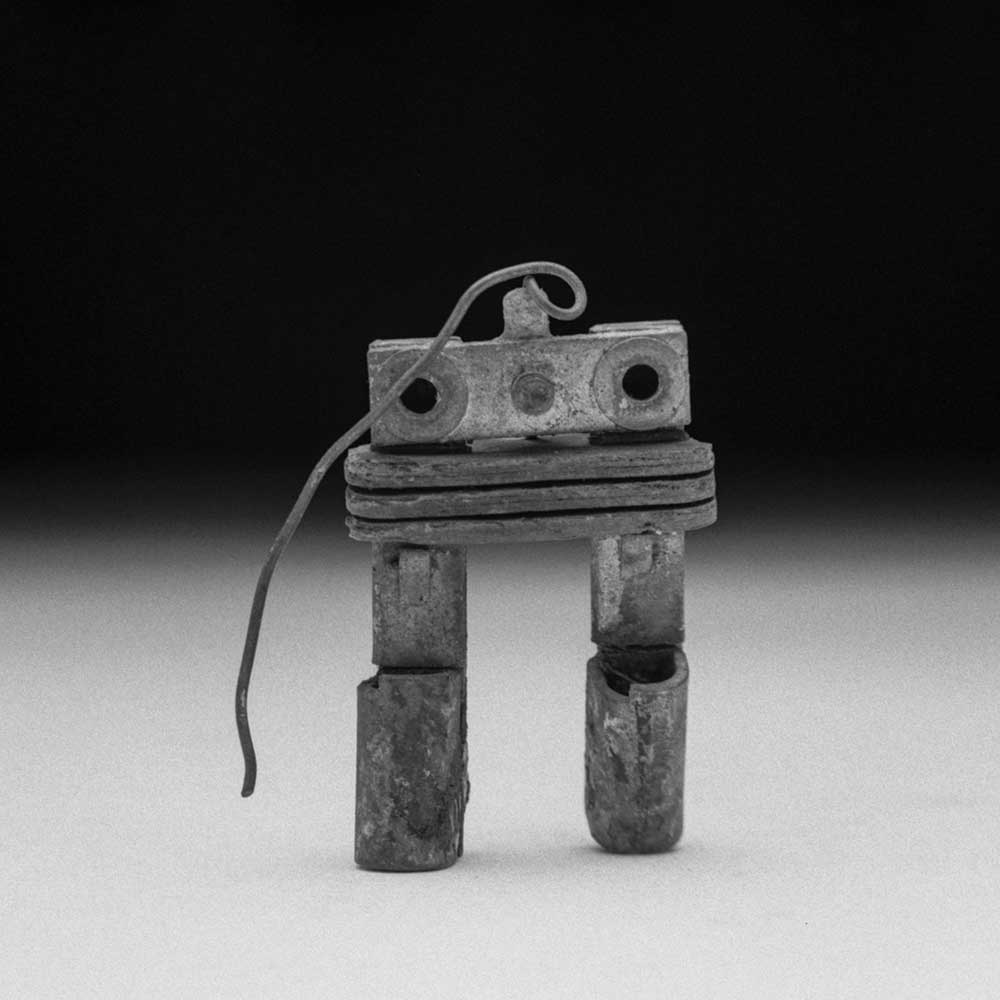

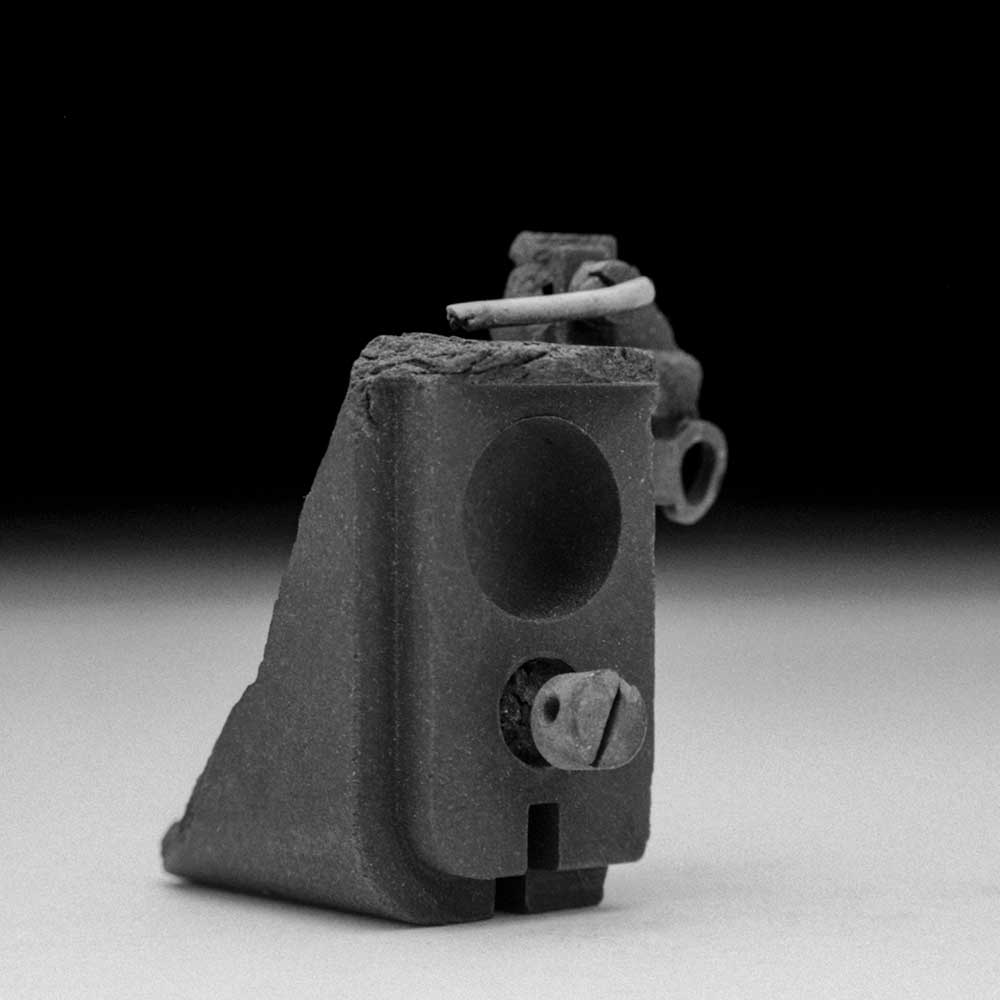

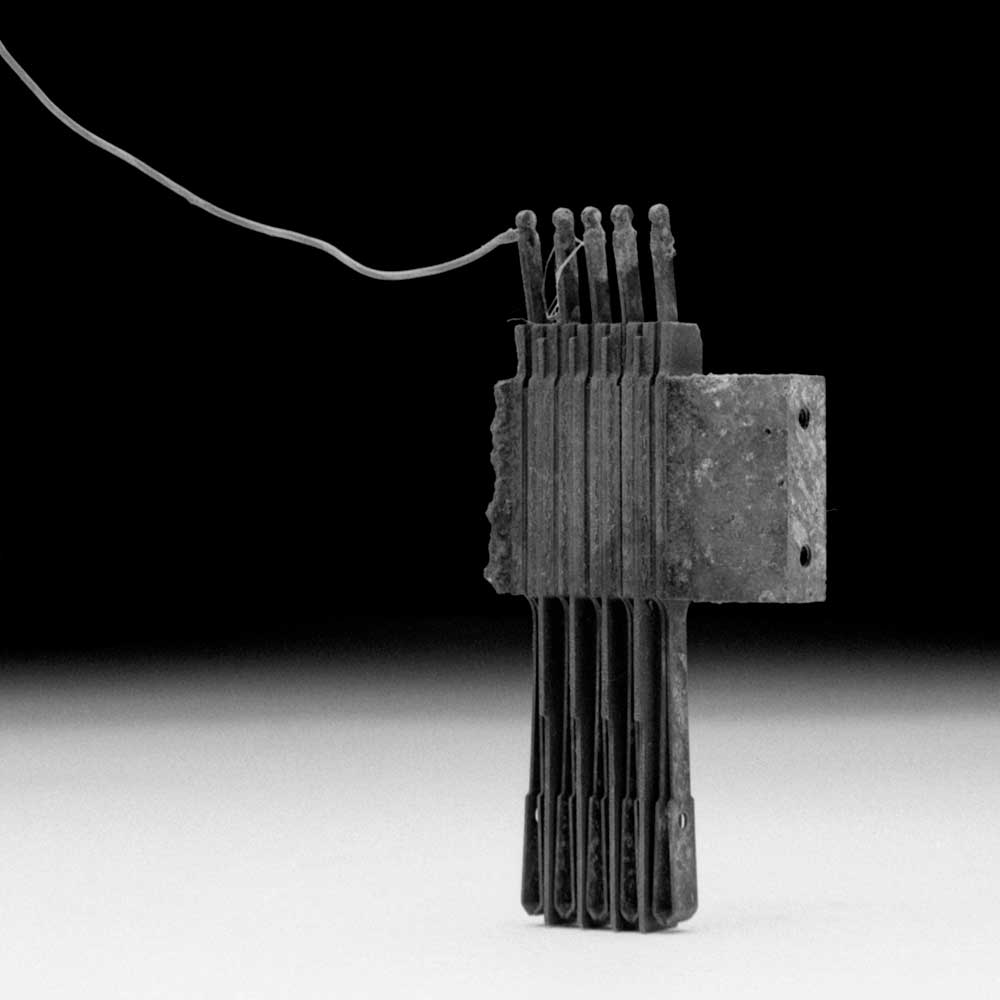

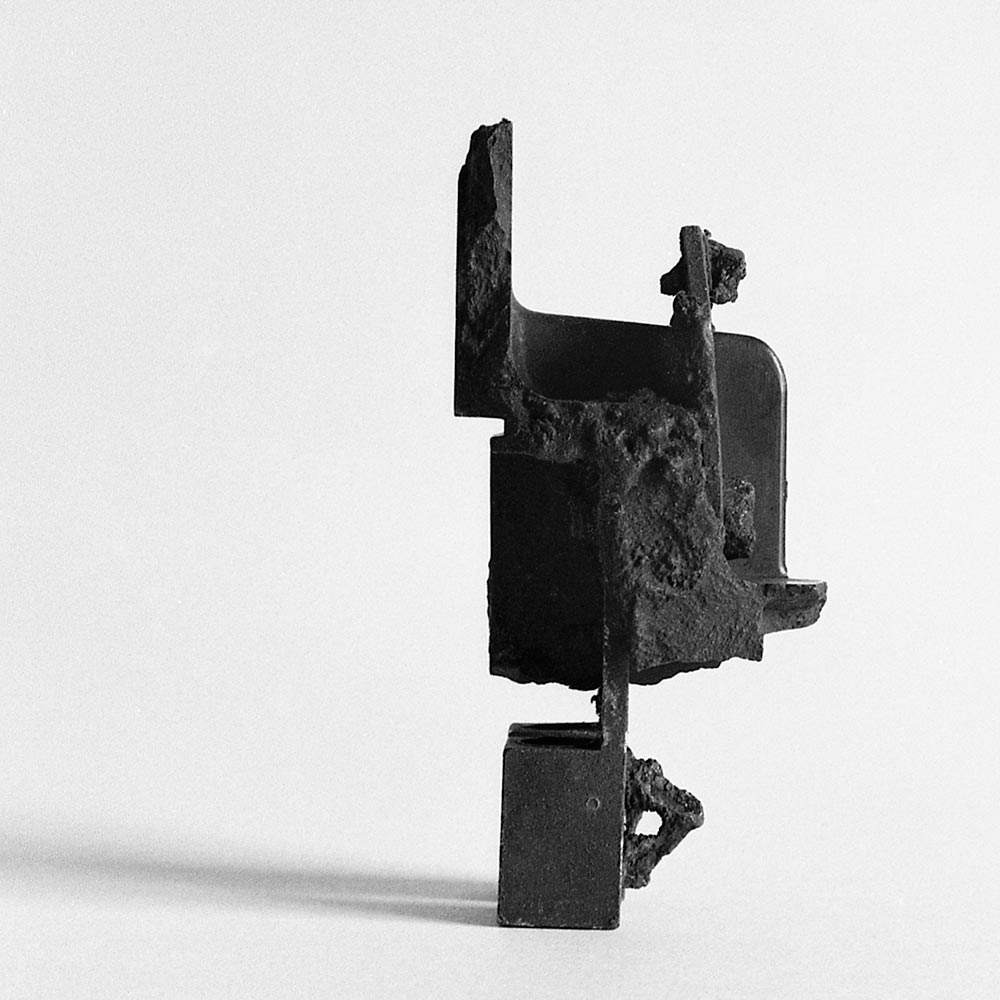

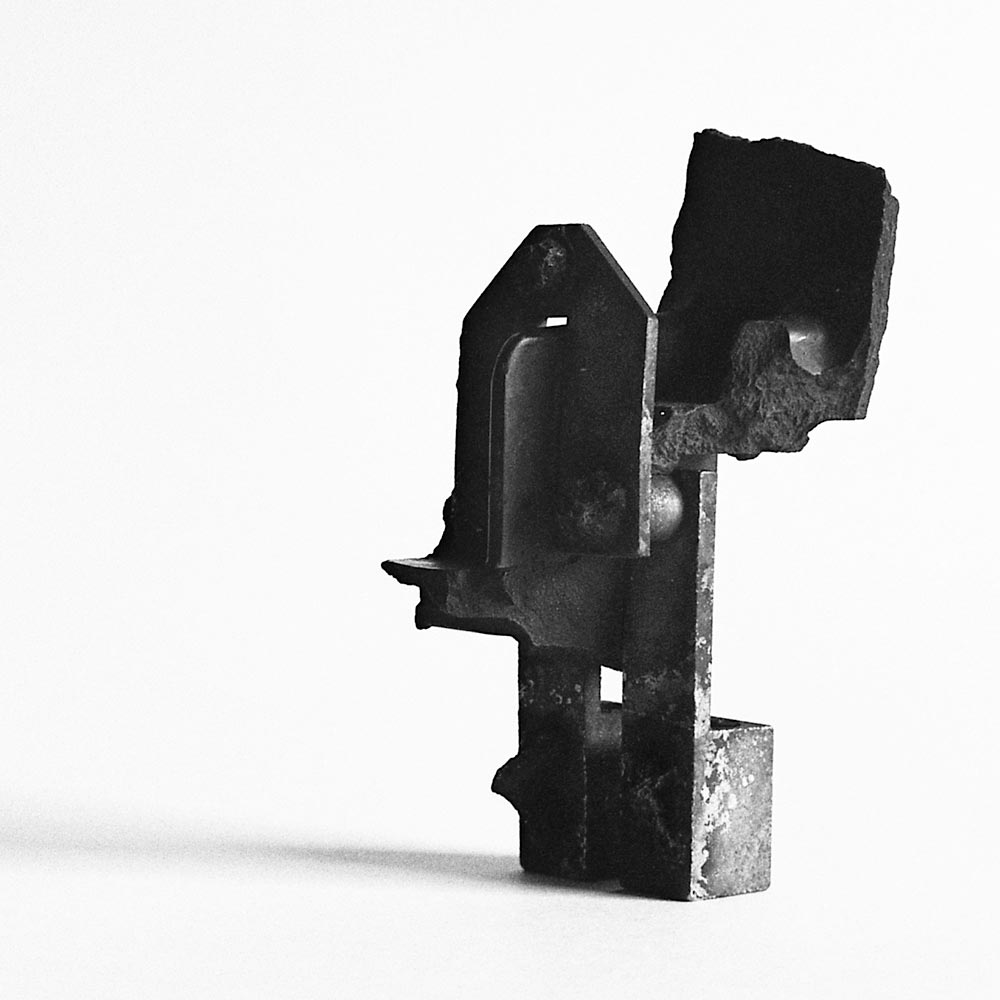

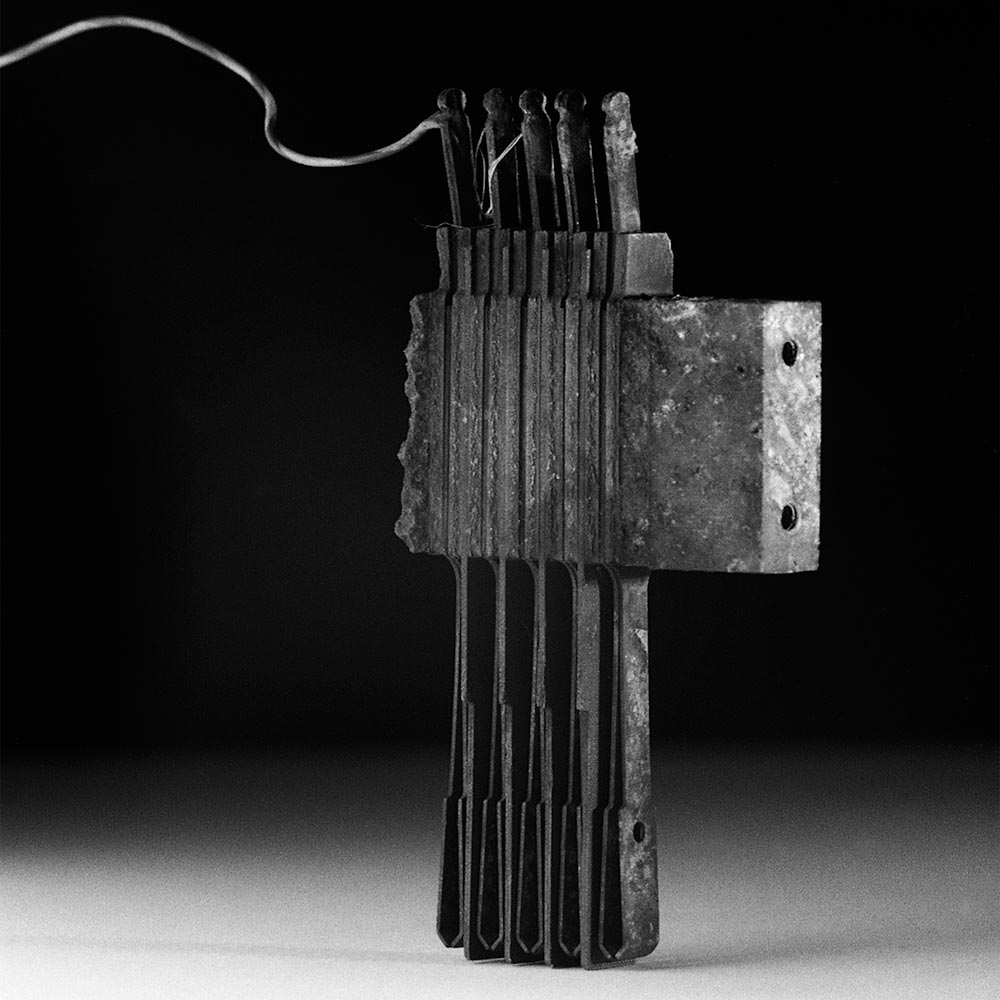

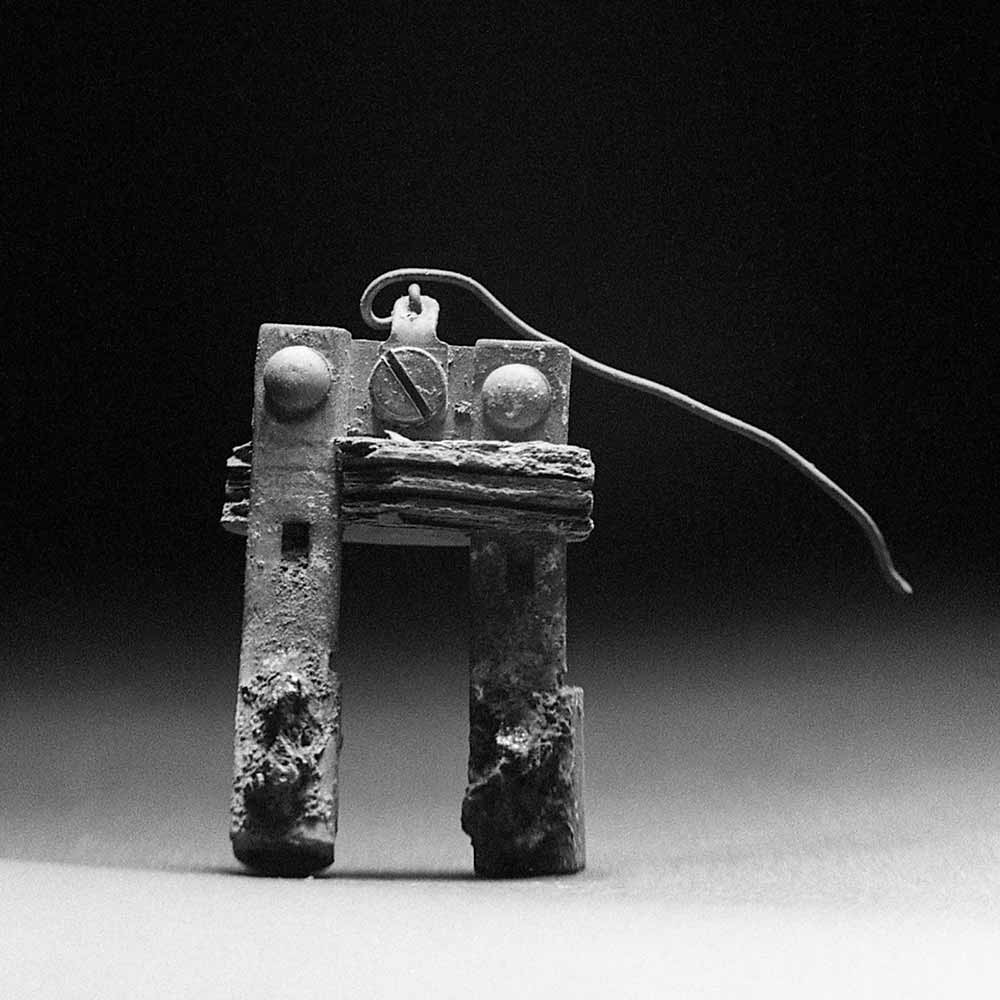

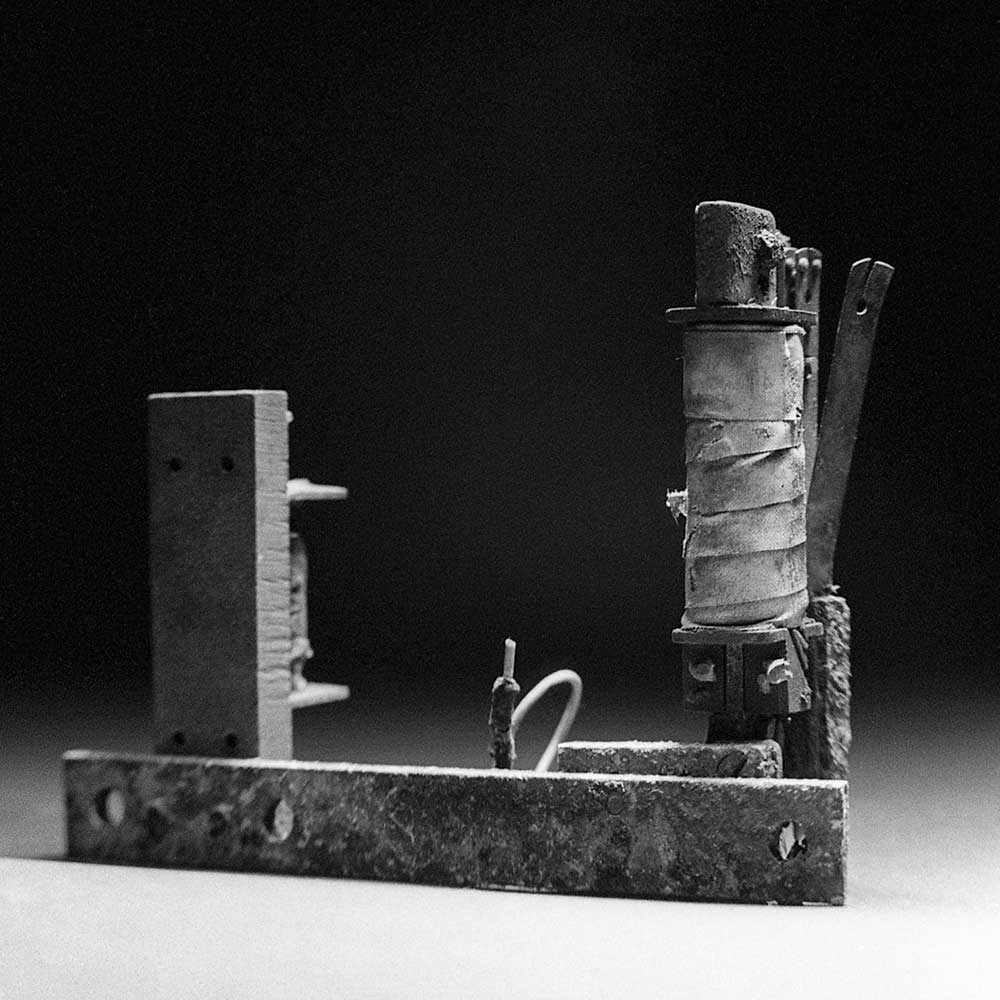

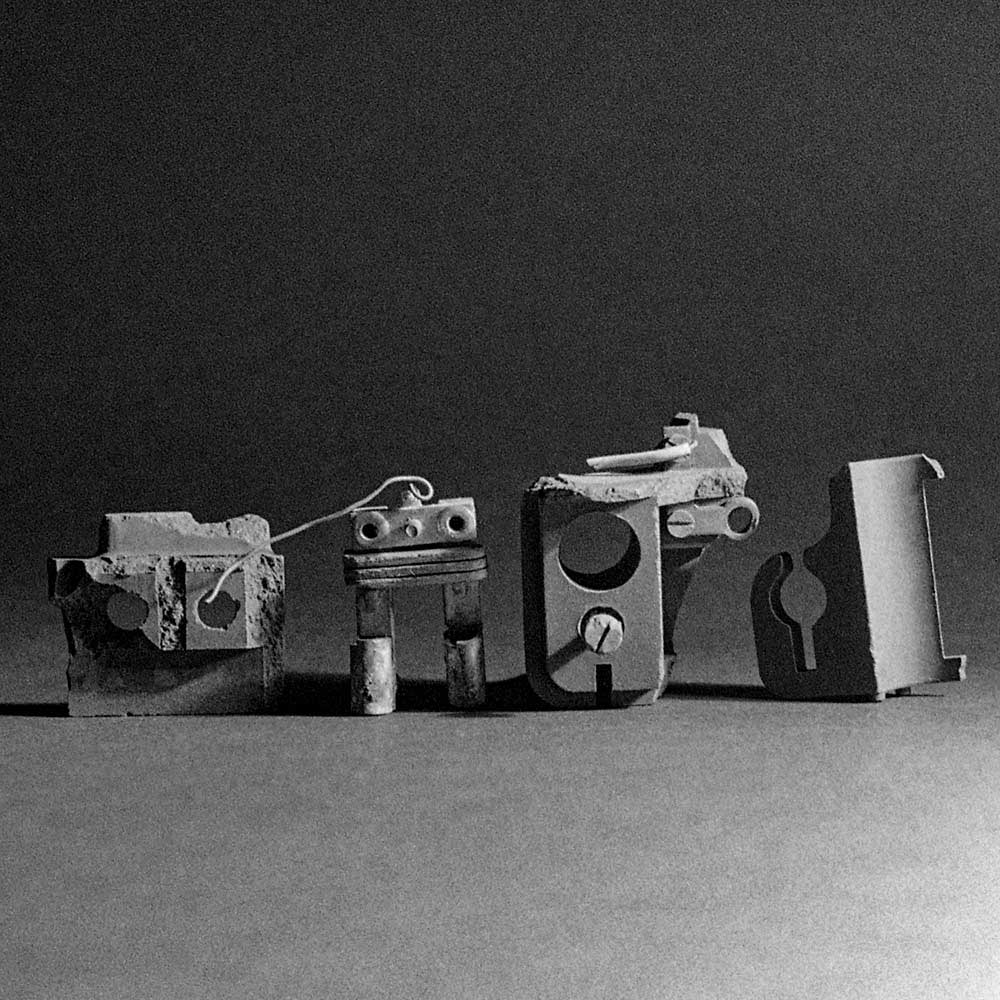

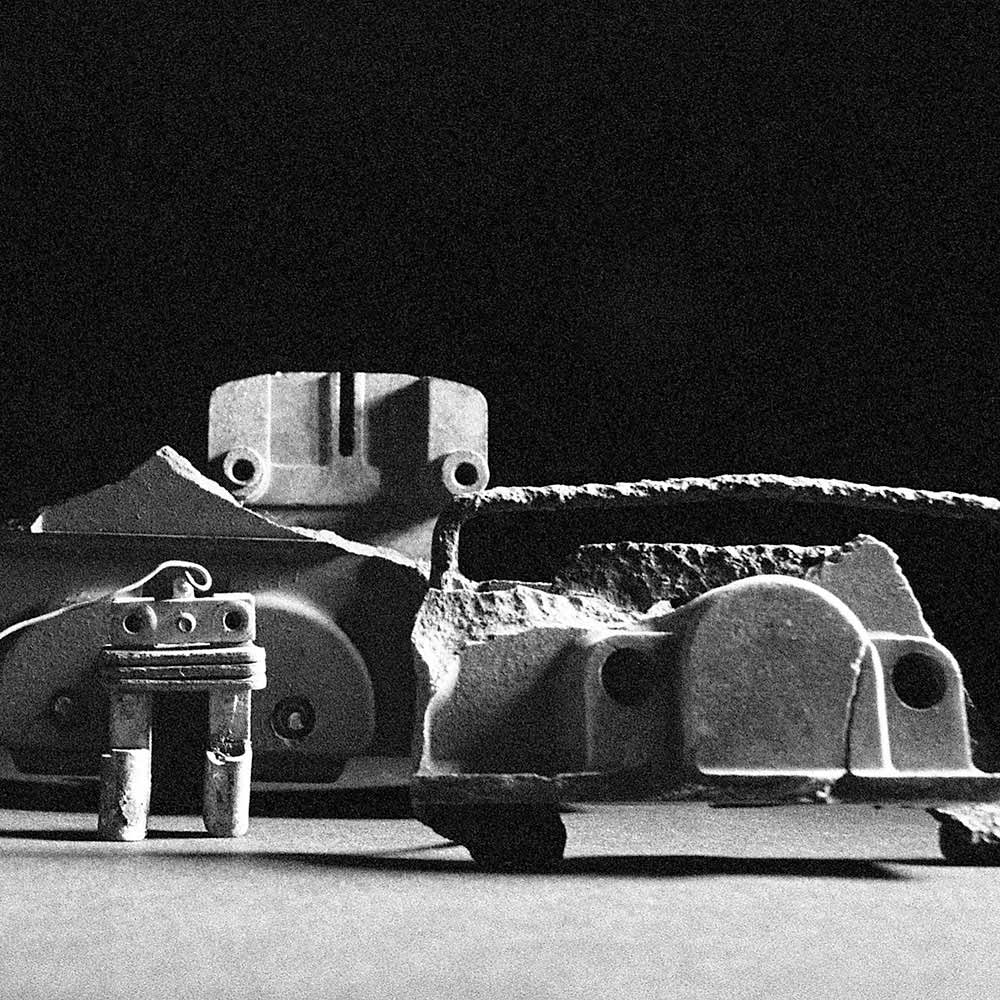

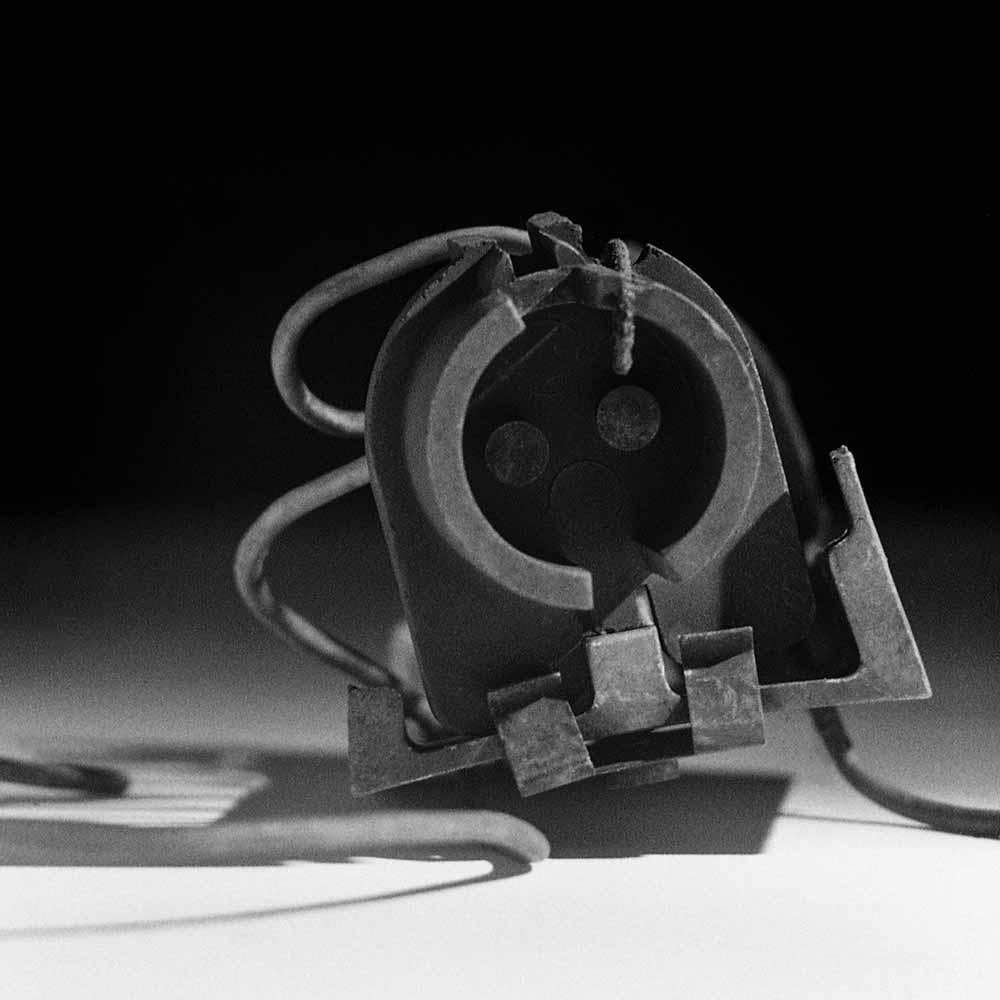

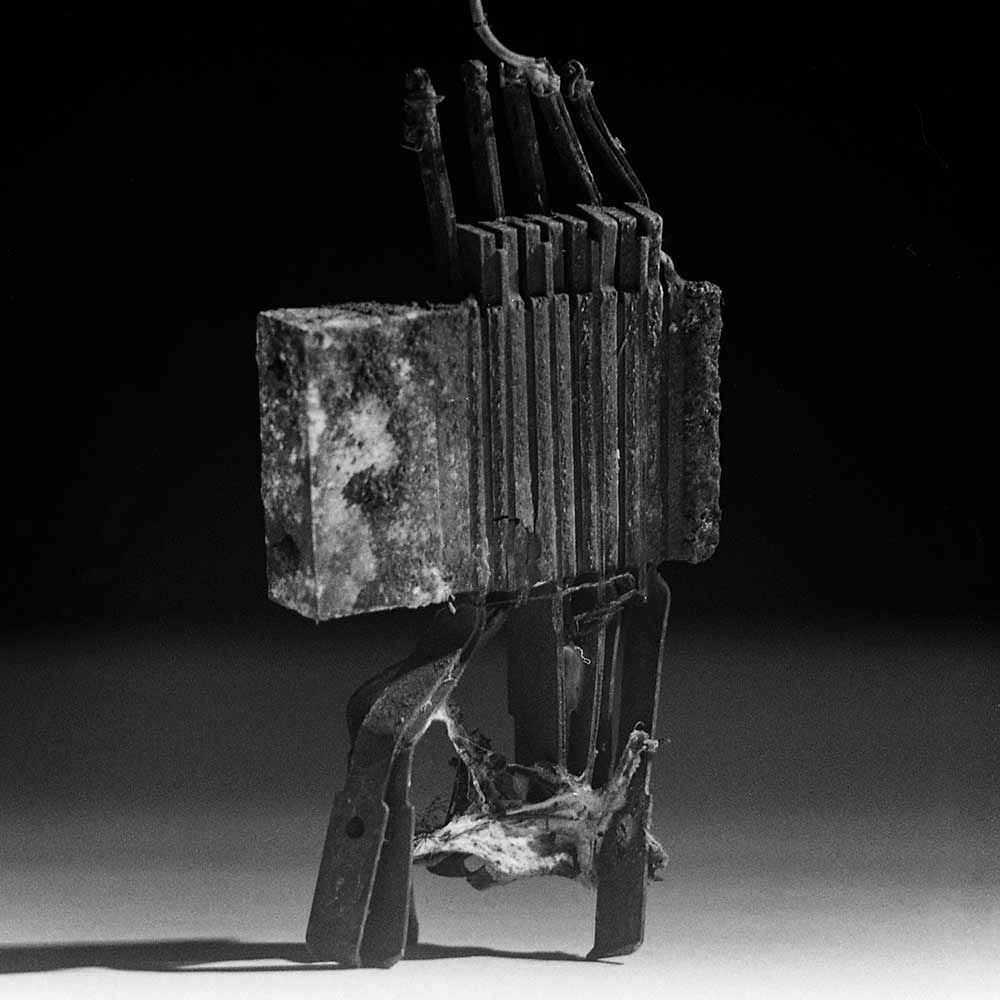

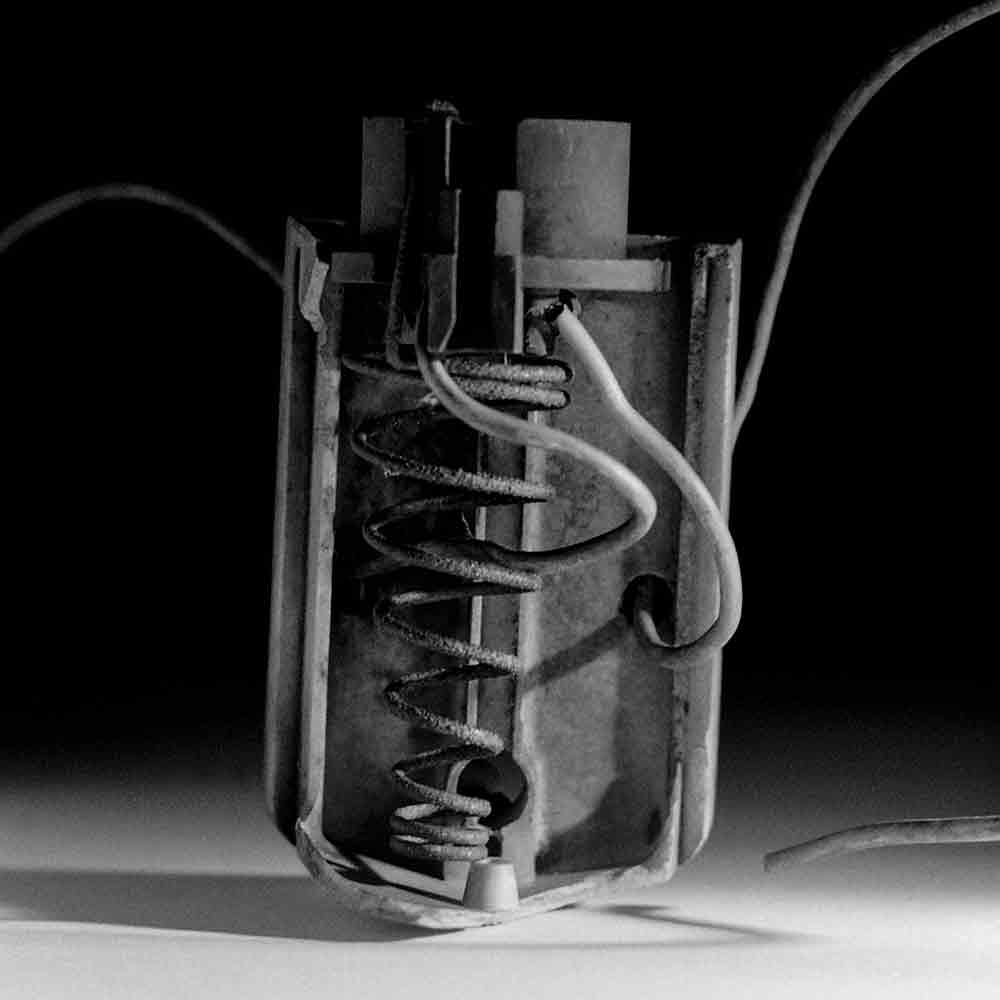

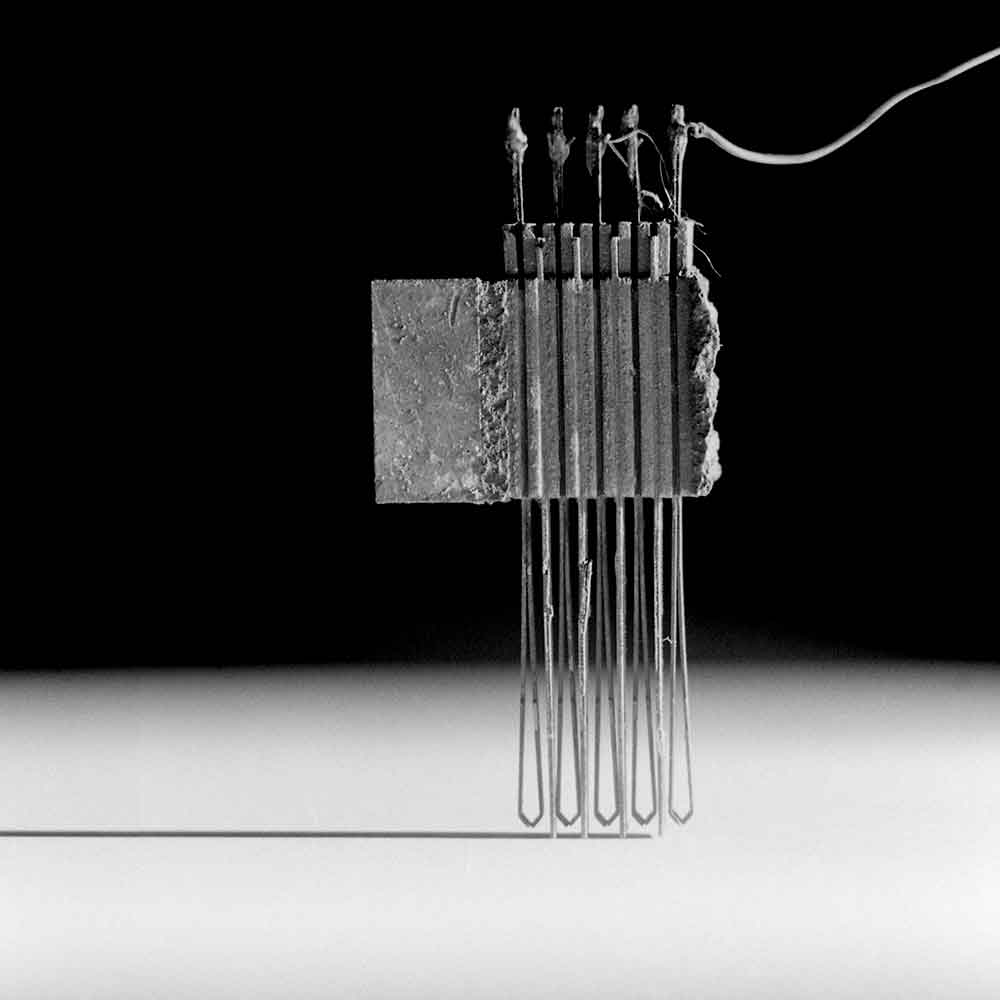

I came to appreciate the delicacy of this work, where the old skills were still required to manufacture functional objects. In the abandoned land around Whitechapel, buried in the grounds of these former rail yards, I uncovered many of these

unassuming objects – the enabling components of an industrial age, long gone, long forgotten.

These small and delicate objects all have their origins in a single handmade pattern; in a sense the DNA code base of their form. For me, they are a reminder that every mass produced item we use today starts out life as a carefully considered, sculpted object. They are the surviving link to those that crafted them and made British manufacturing the power house that it was.

Returning from work at Cartier in New Bond Street, I would turn over the broken asphalt; the bitumen soaked,

sulphurous ground in the abandoned Whitechapel yards, picking objects out of the toxic earth. I would cut sections through the seething ground, hundreds of rescued items were given a wash in the bath of my local tenament squat, before being dried and photographed in my make-shift studio. My flatmates moaned and moaned – but I replied "how else are you going to see these things at their best if you leave them coated in toxic slurry?"

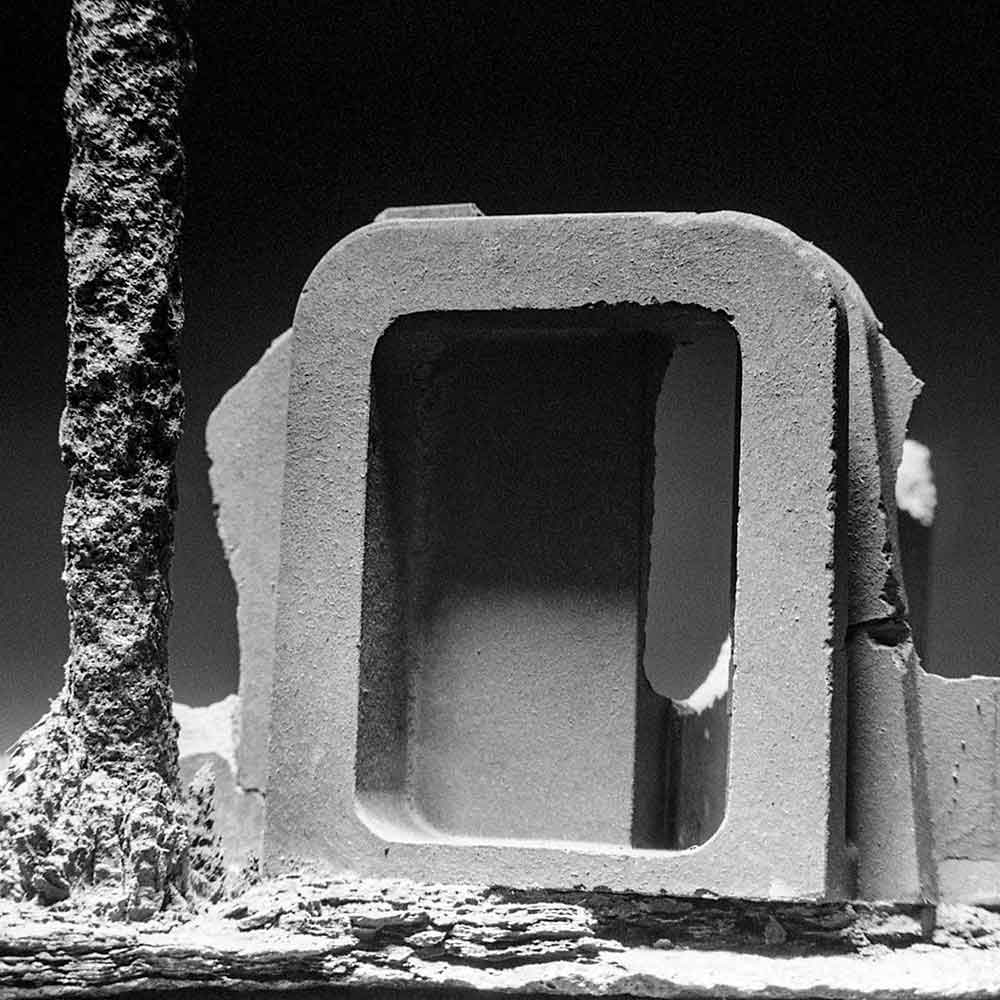

I feel that the result is remarkable – the bakelite objects, switchgear, light fittings and machine parts were all treated with a reverence which imbued them with the same significance as the jewellery I was trained to create and to conserve in my day job. I photographed them in haunting, solitary, geometric elevations, balanced to create intriguing compositions. The intentional lack of referential scale and low viewpoint of the photography, tends to liken them to ‘totems’ – much larger objects than they really are. The surfaces, scratches and broken edges reveal their delicacy and careless abandonment.

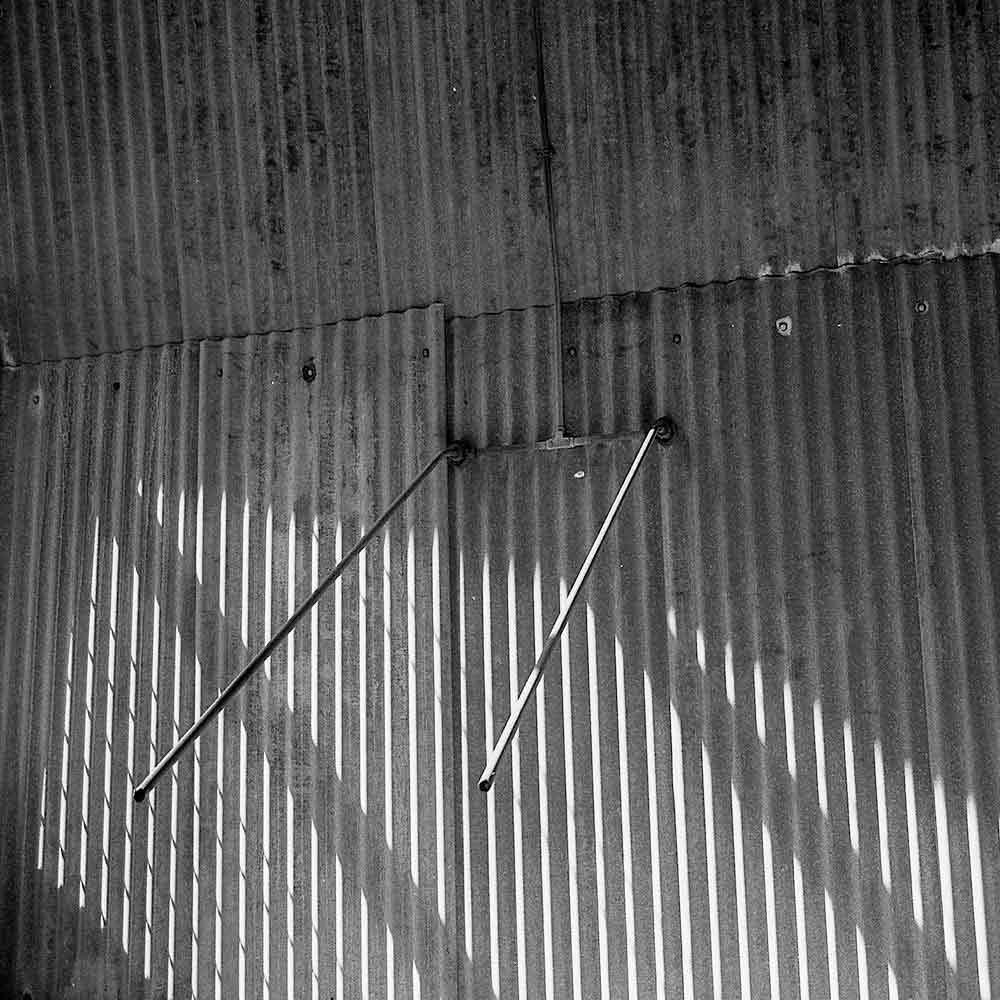

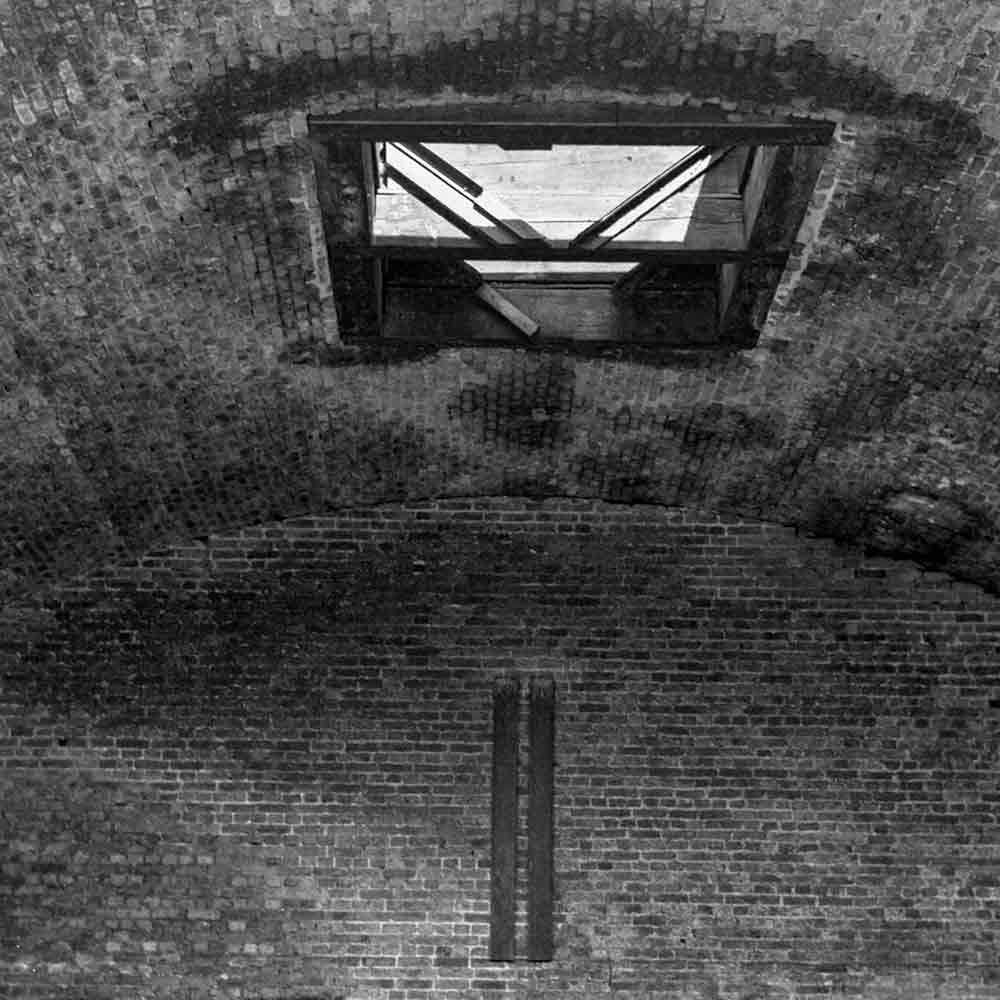

The objects are photographed in the same light and shadow as their buried context – the sheds and arches of the railway yards. I recorded these spaces too – these tombs, the burial chambers, the looming rooms and crumbling walls that contained these objects. The arches and yards are now long gone, replaced by schools and blocks of flats – these images the only reminder of their existence.

This photographic series has remained intact and I have used it throughout my working life. It has been used as the creative basis for graphic design work for television and the series is the inspiration for new oil paintings, etchings and collagraphs. The object of my present work with the pieces is to try to reimagine them as more natural forms, looking back to how they might have been and extending their original design into flowing organic structures.

Thanks to Ian Thompson, who convinced me of the value of the work, created the original blog about the project and offered generous and enthusiastic support.

In the autumn of 2022 a new series of larger oils on board was begun, based upon these images. They should emerge some time in 2023.

Any questions?

If you have any questions regarding this blog please send me an email.