Travelling north east, leaving the rocky coves of Penwith, the sandy bays of St Ives and Godrevy, and dunes of Hayle behind, eventually the coastline again becomes more remote and intimate.

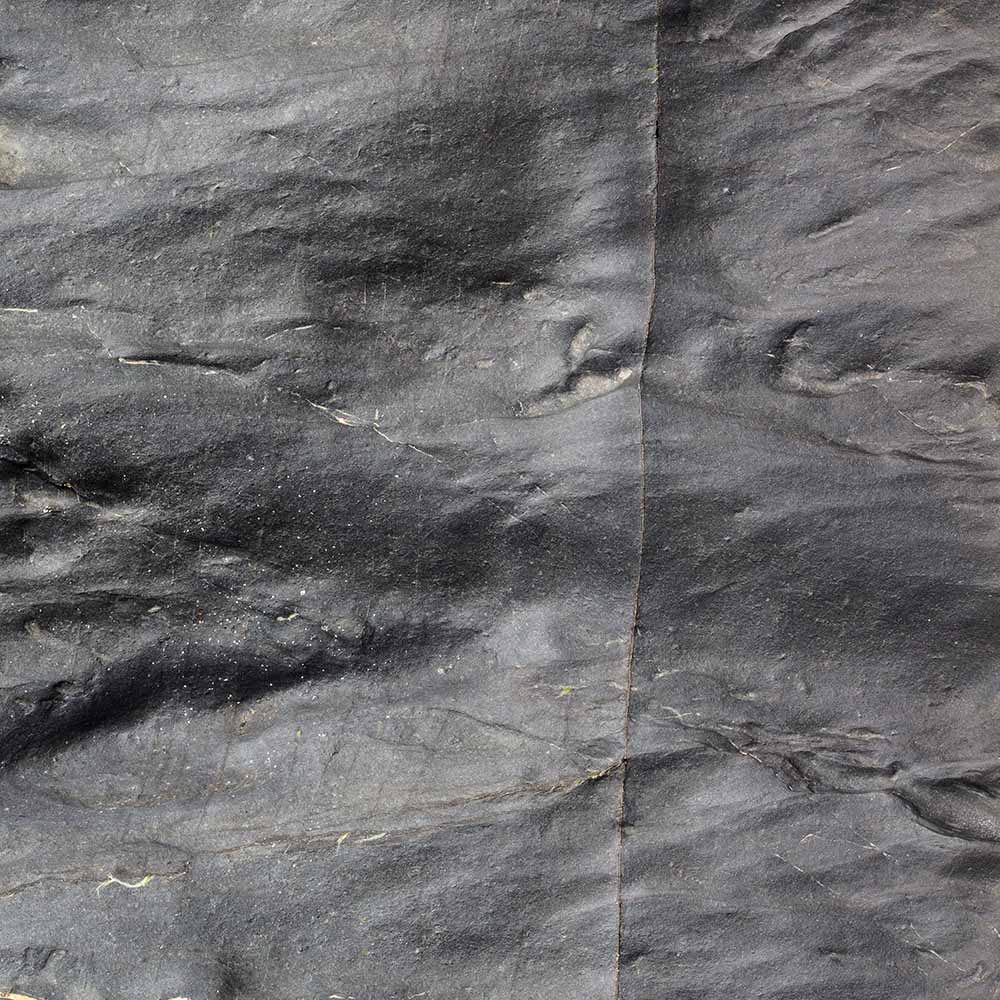

Our stretch of the North Cornwall Coast really begins at Trebarwith Strand, on past Boscatle, Beeny cliffs, Strangles, and so to Crackington Haven. Here we find the contorted strata of ancient rock formations edging the coast, then on to Widemouth Bay. As its name suggests, a wide bay of sand and shingle, but once again backed by rock formations that at twilight might convince the visitor into thinking they are in another world. Beyond the beaches of Bude we enter Devon to find the coves of Northcott Mouth, Sandymouth and the romantic Coombe Valley. Leaving the listening station of Morewenstow we arrive at Hartland with its huge spherical rocks, so similar to those of Priest Cove, Cape Cornwall. We have seemingly come full-circle.

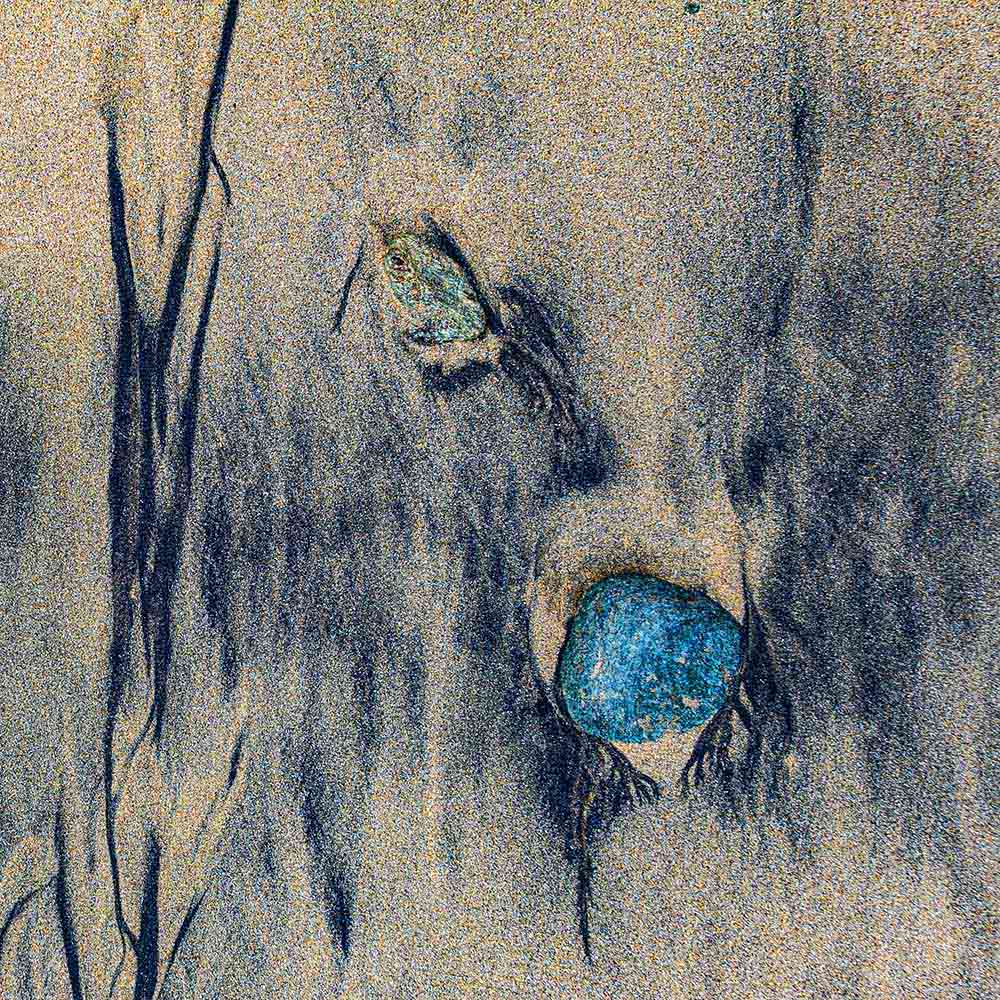

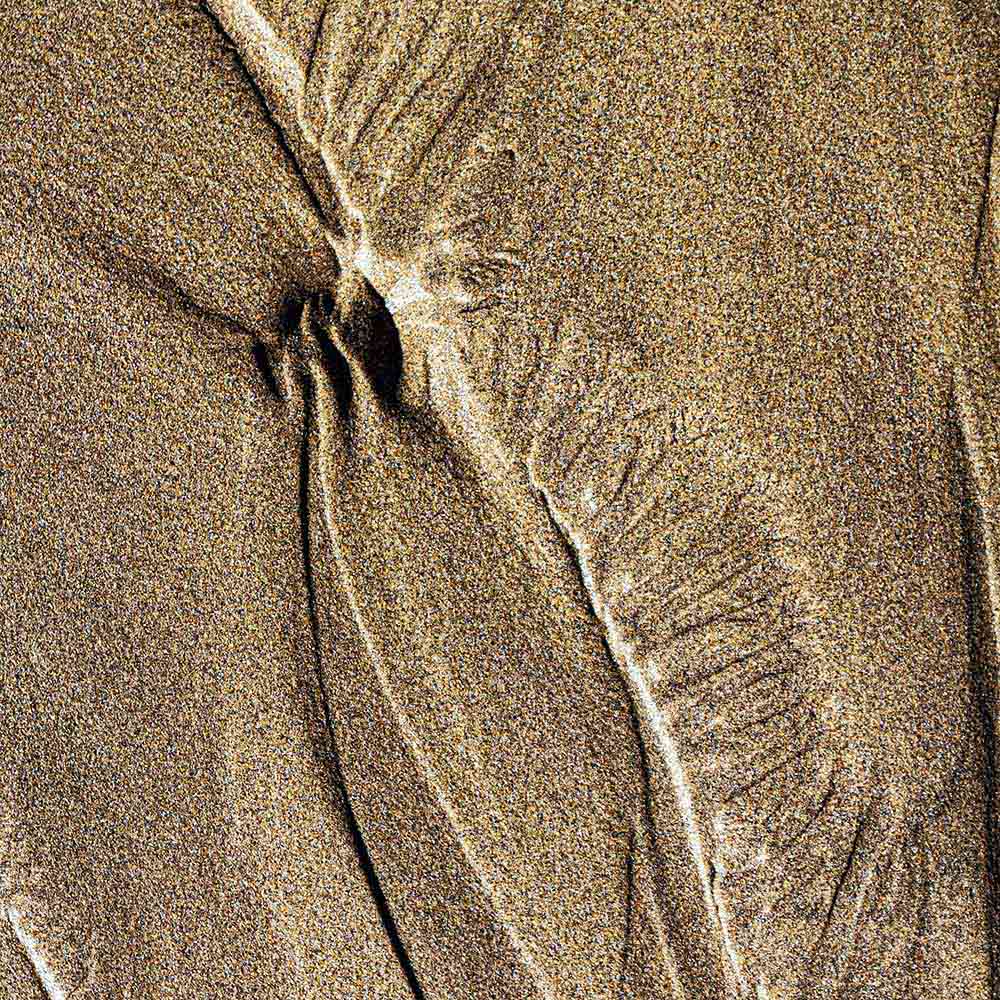

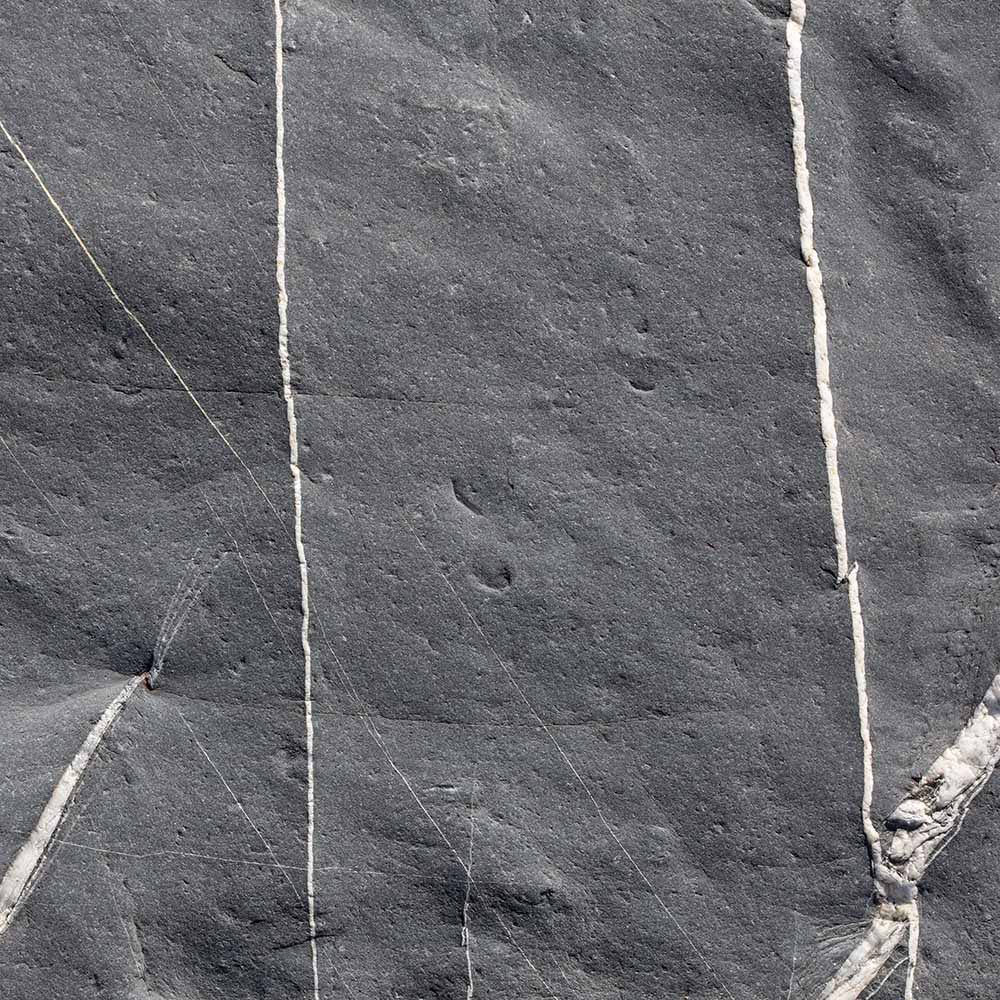

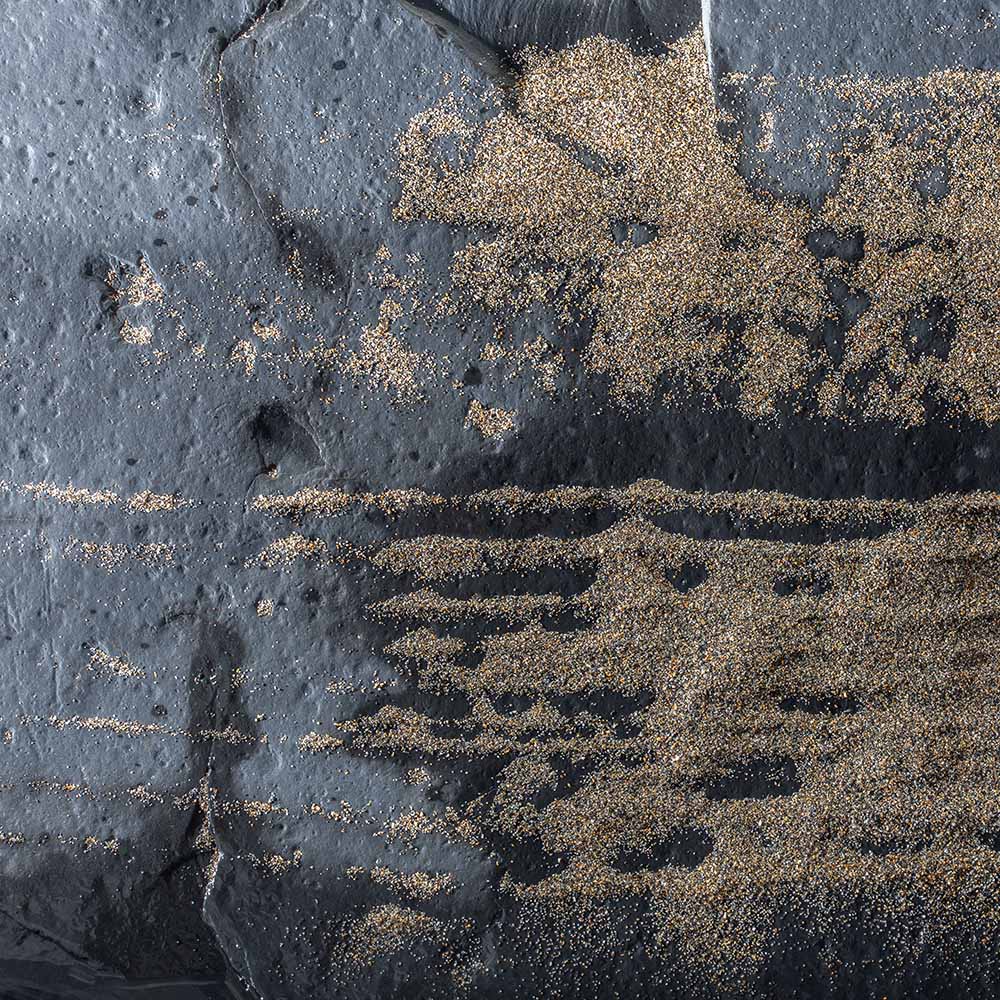

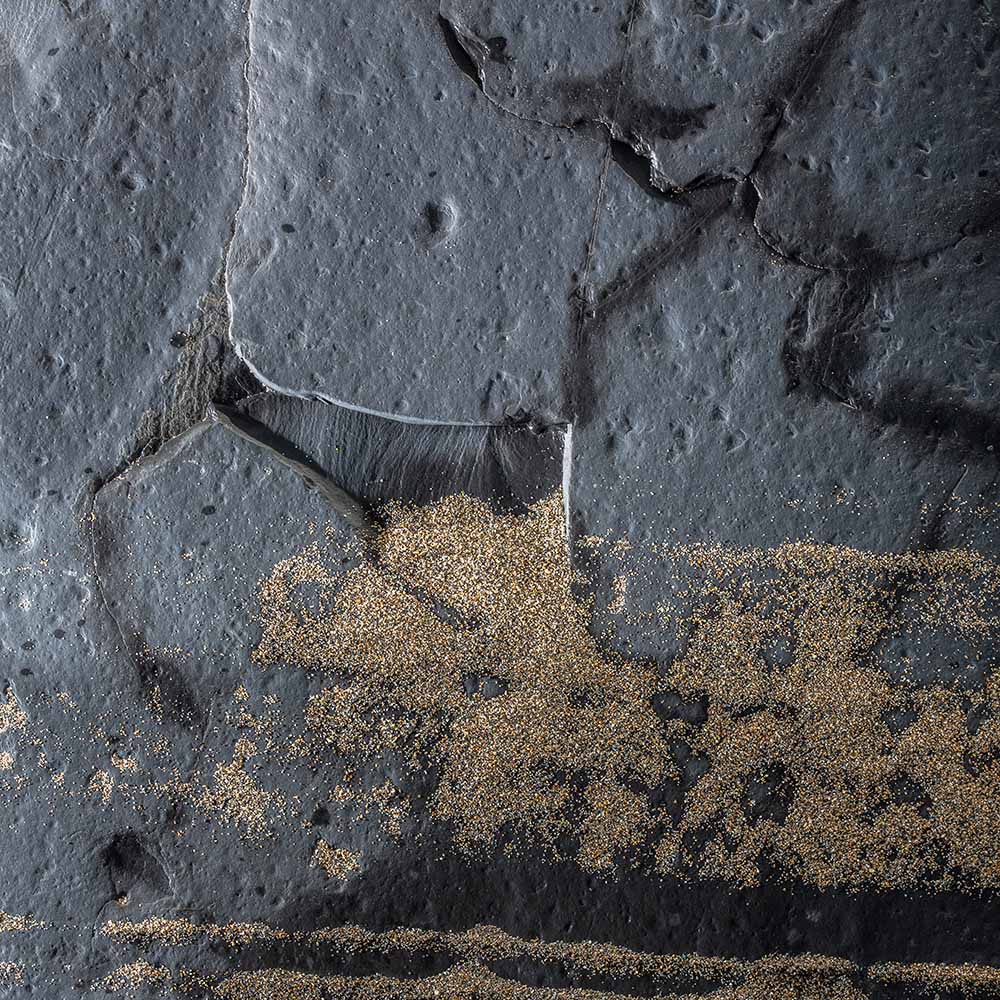

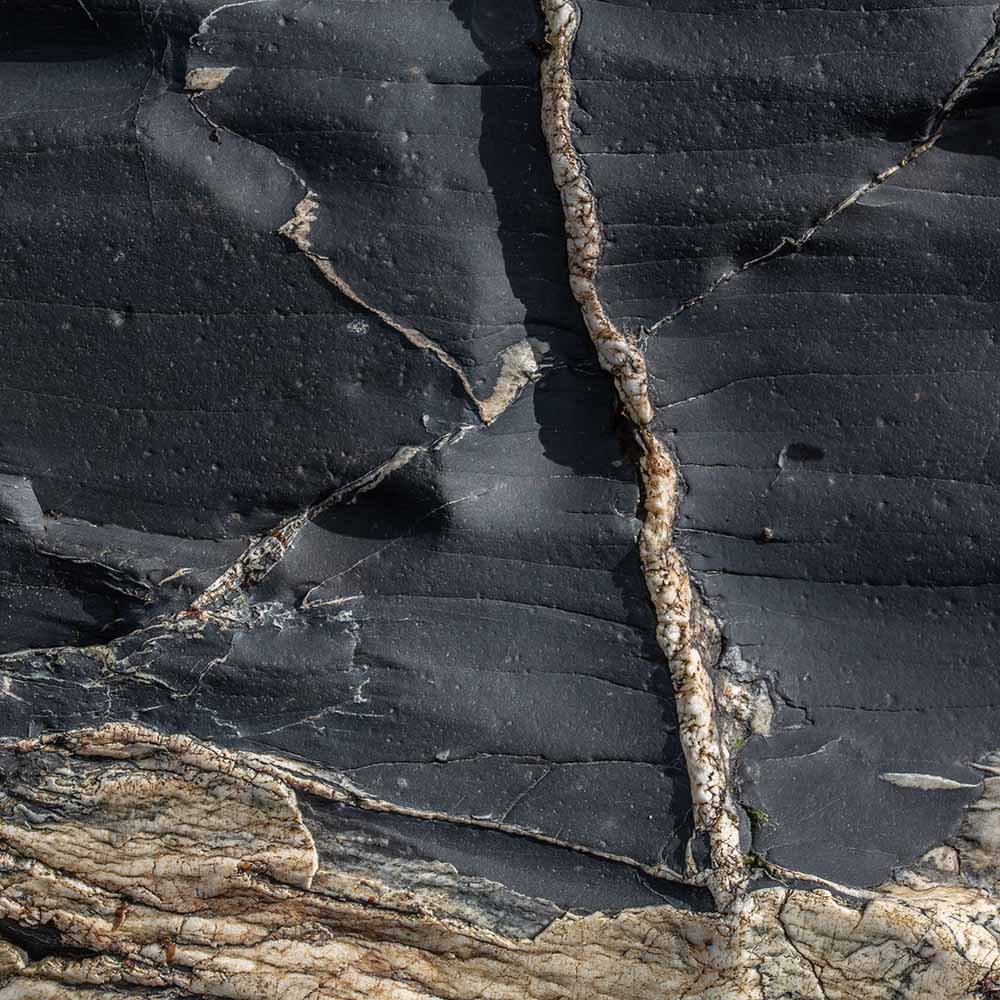

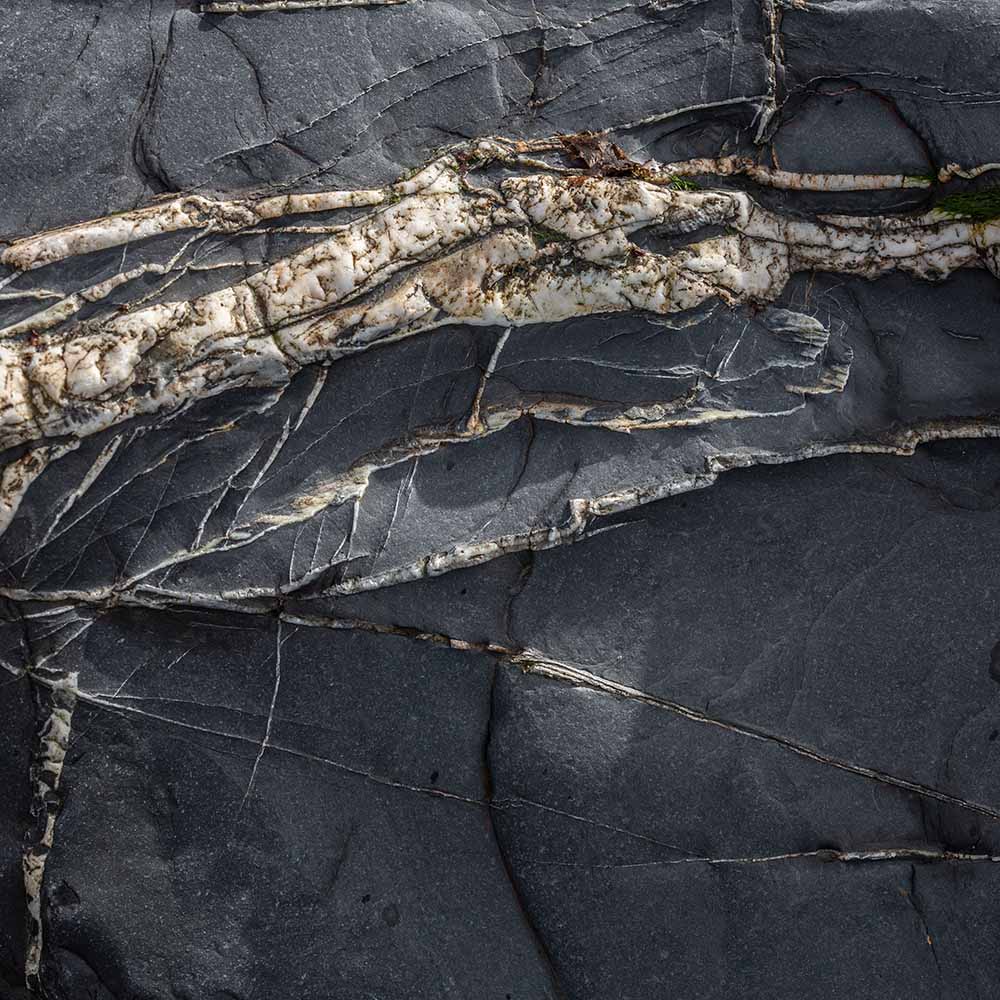

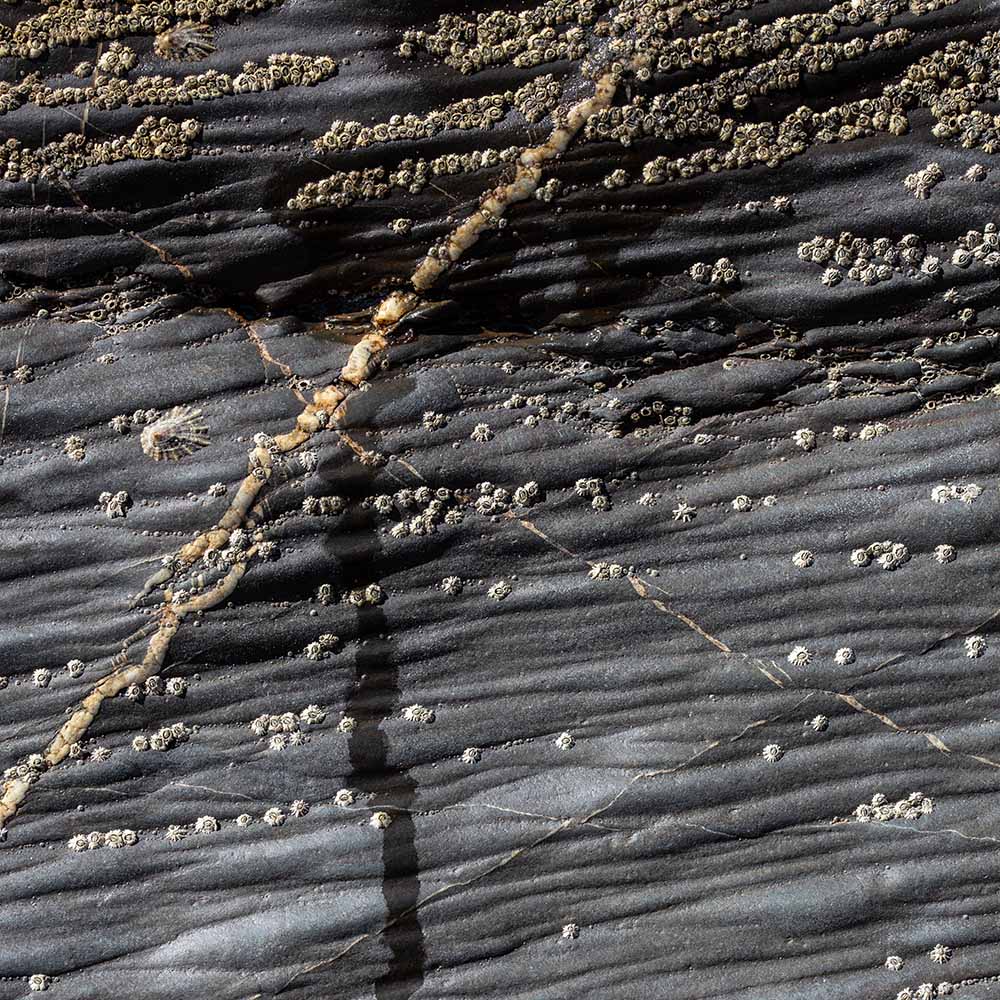

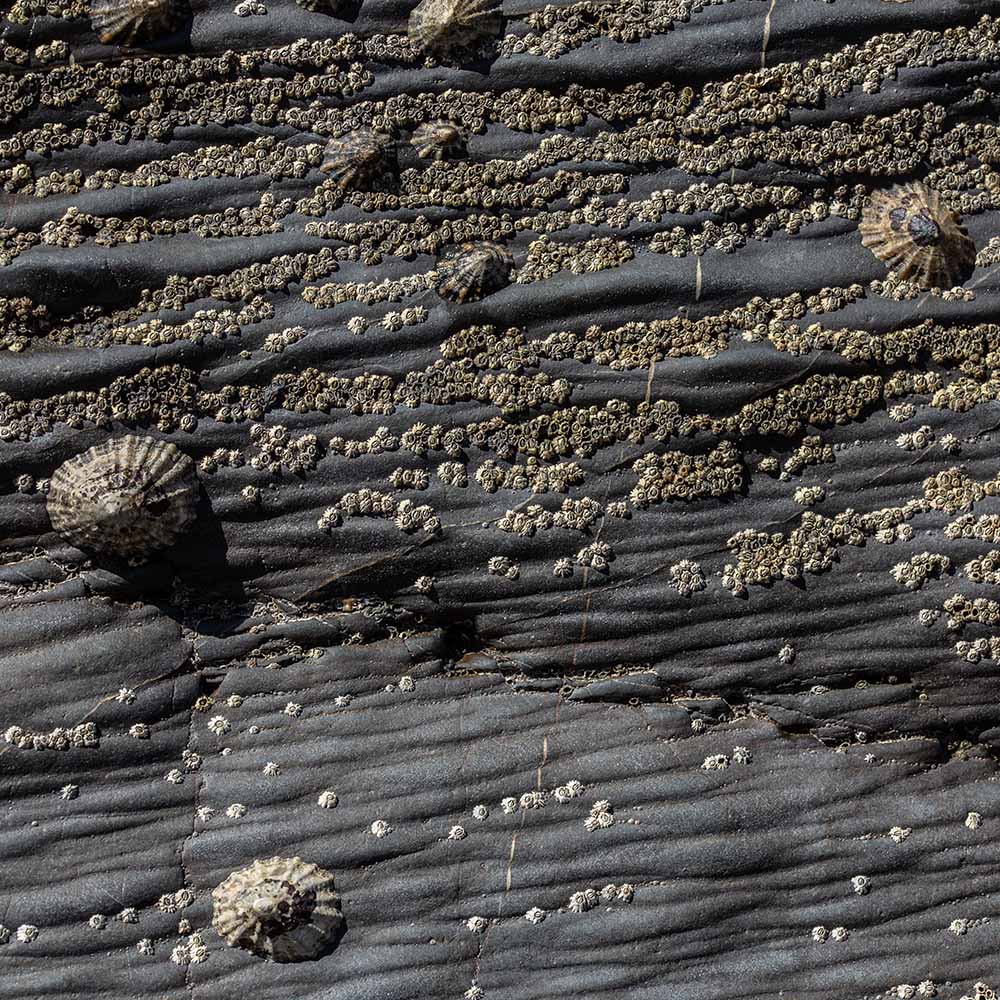

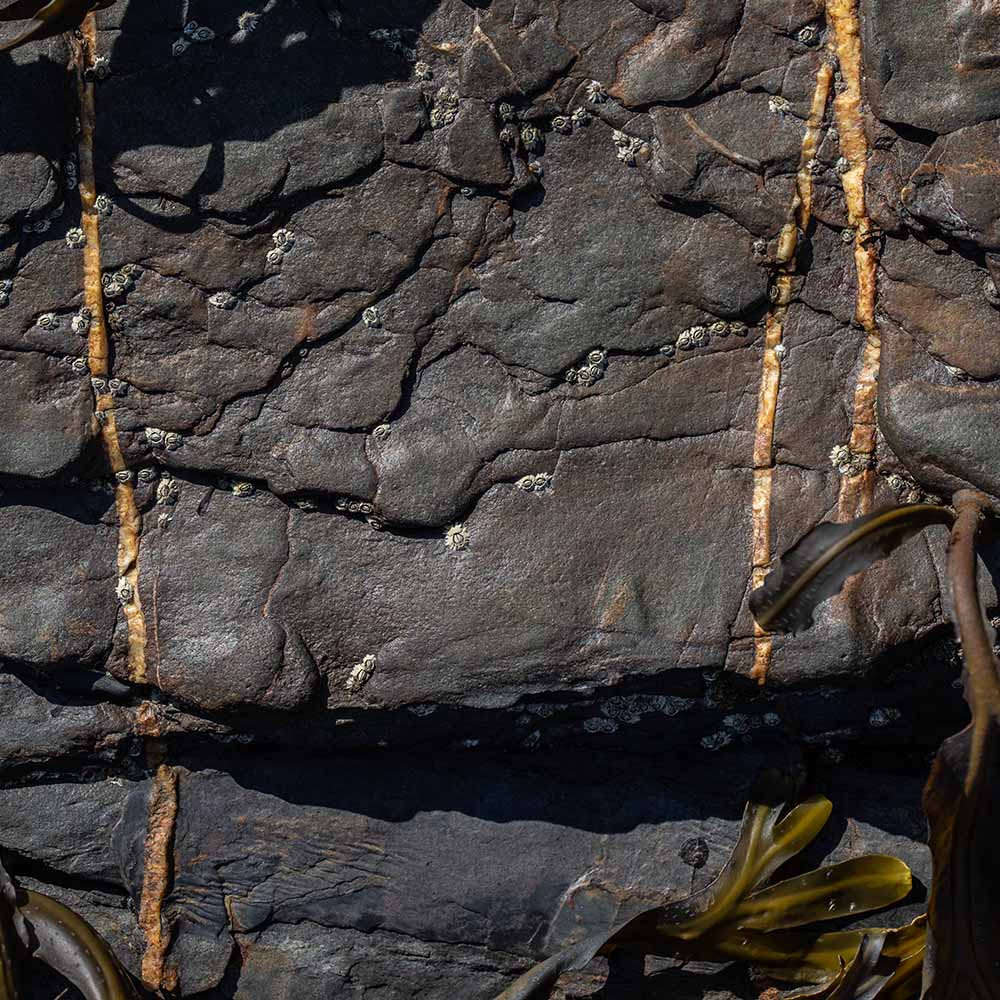

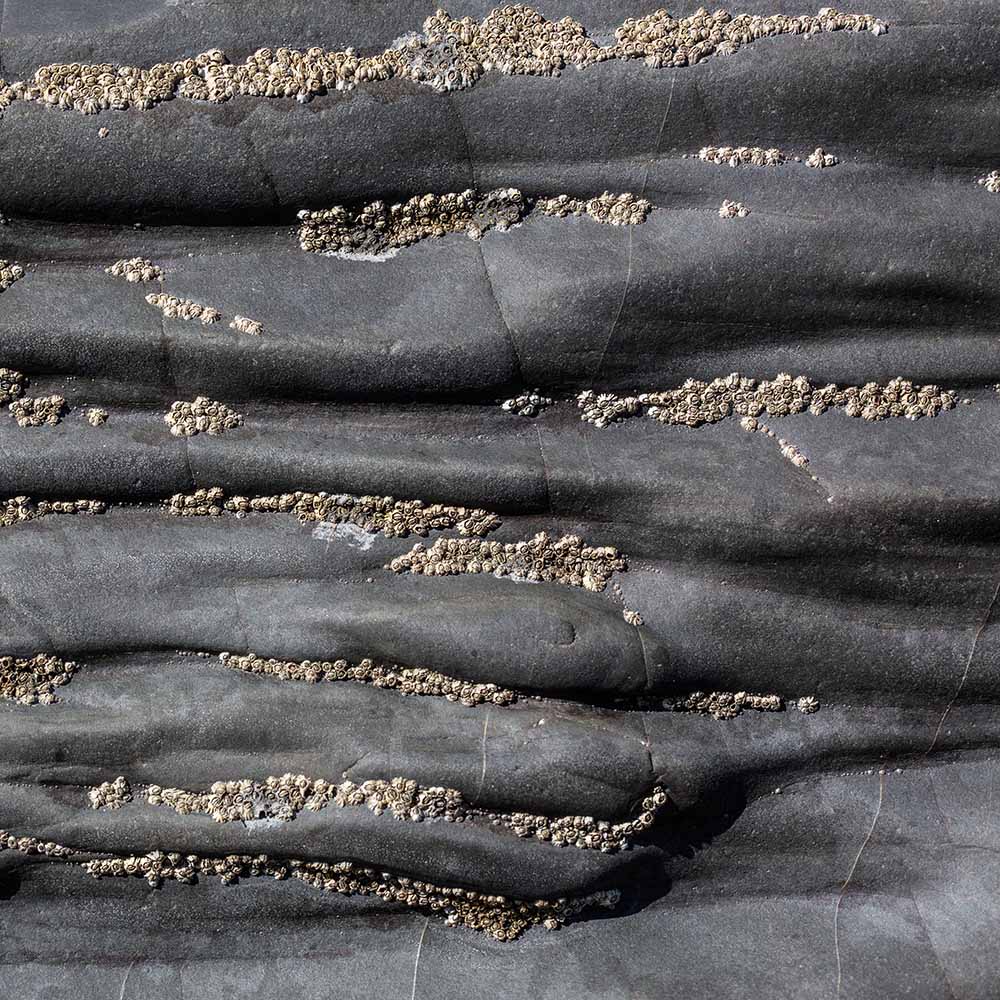

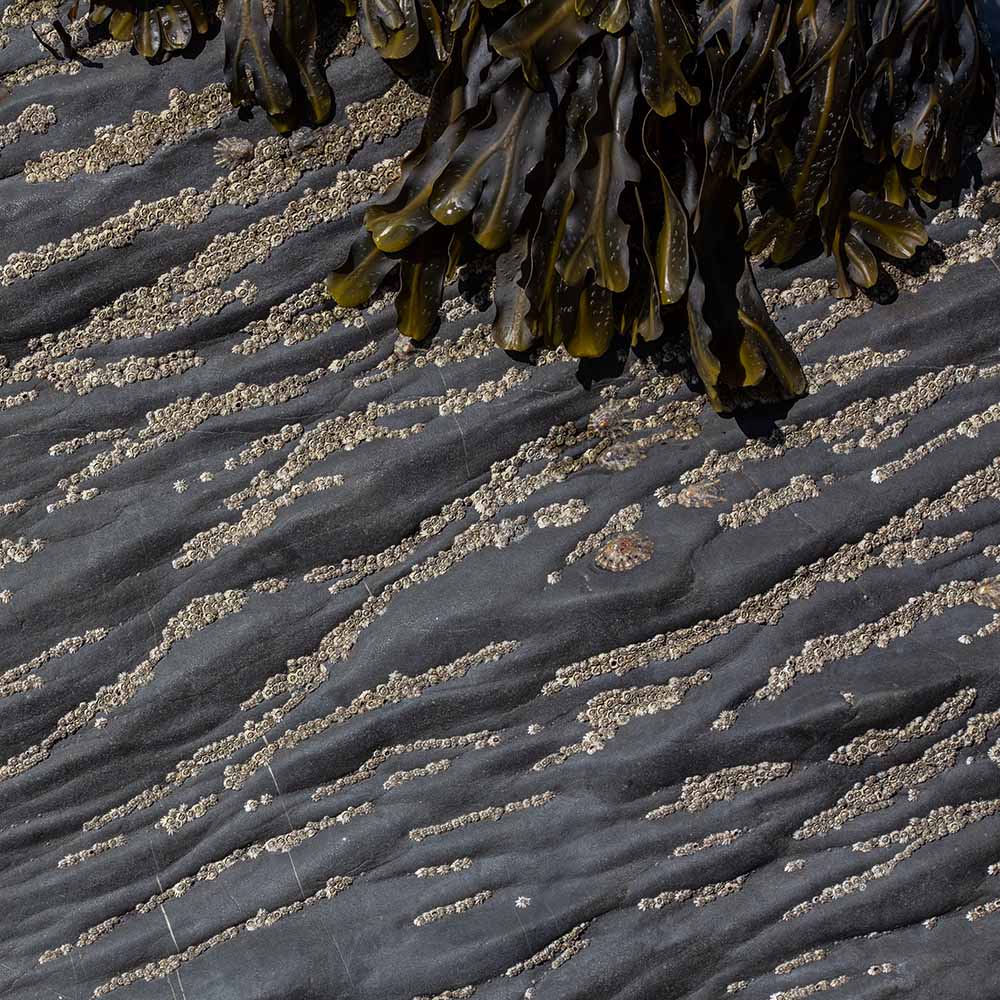

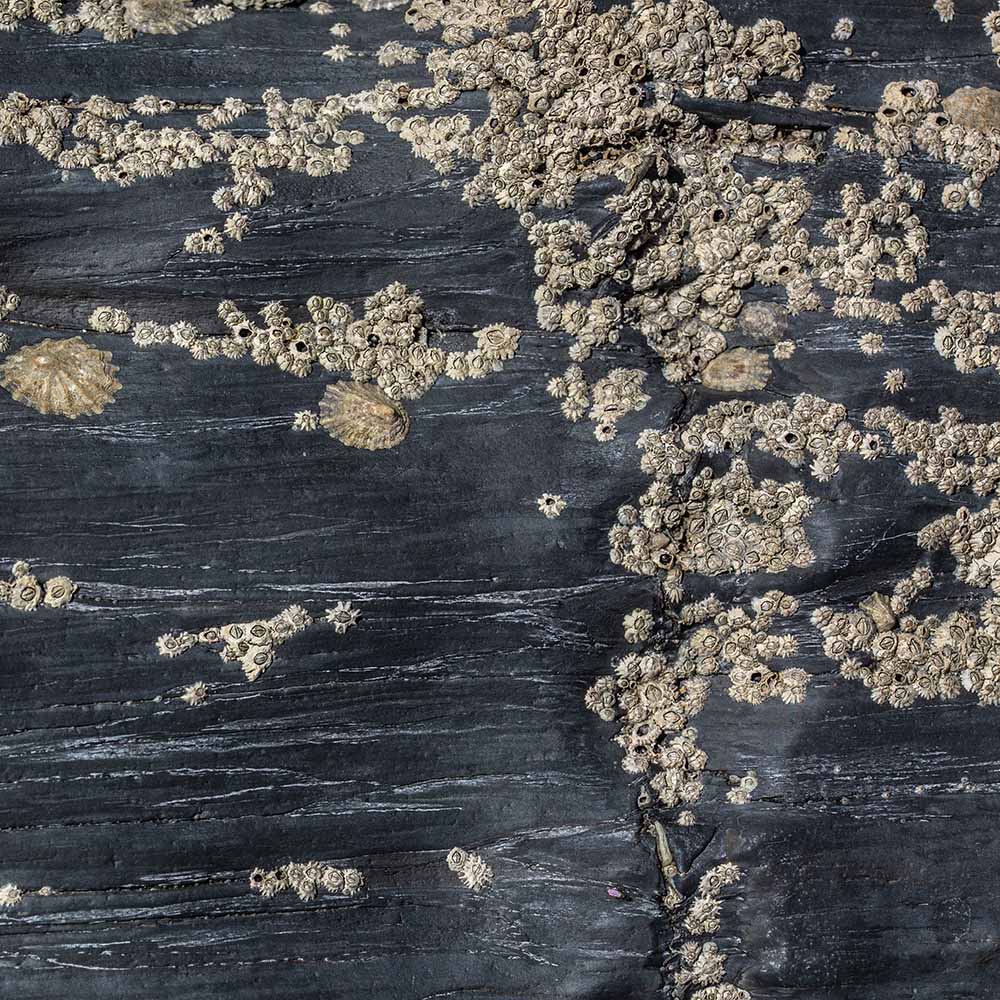

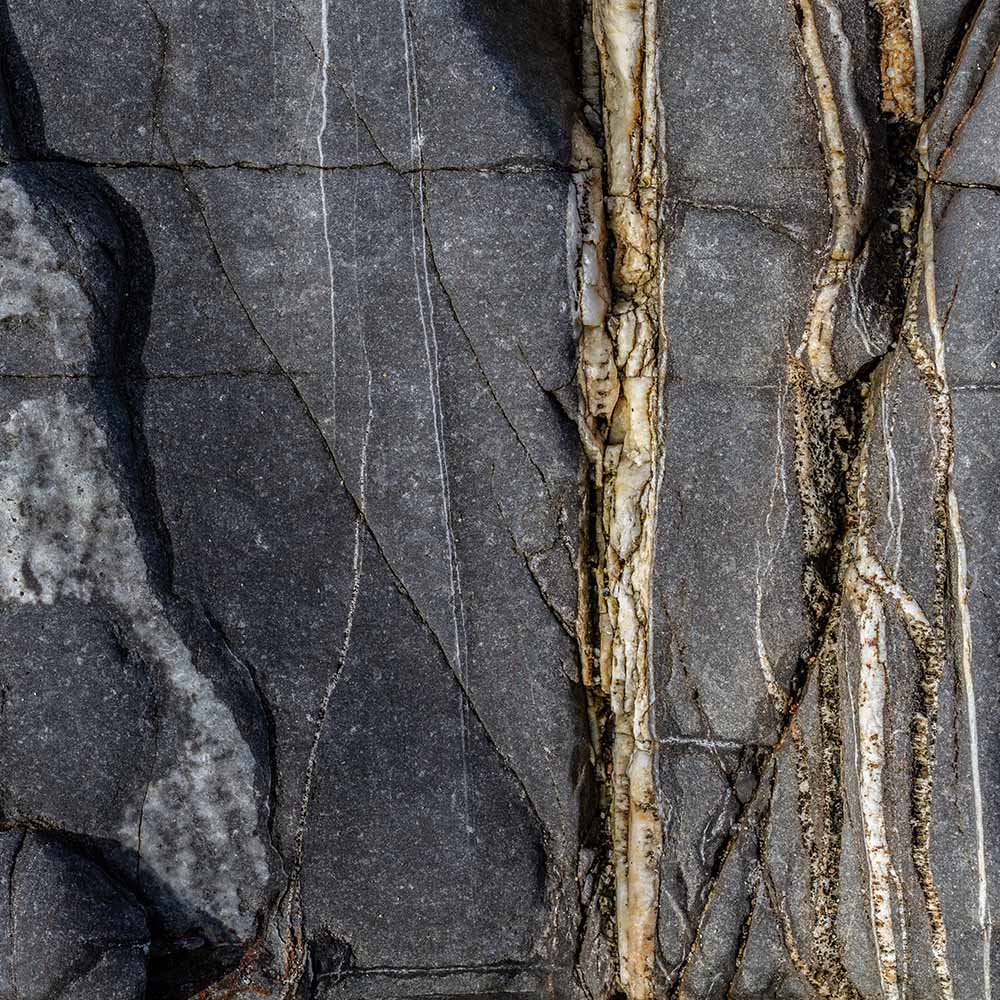

One could make drawings of the rocks, stones, and marine life and them produce paintings to resemble the images seen here. But during countless visits to these beaches I came to realise that it was not simply the beauty of the formations as we see them now that interested me. The geology behind these forms has been at work for millennia, laying down sediment, compressing the rock, folding, fracturing. Then hard quartz and other minerals have been forced upwards, along the weaknesses and fissures lying at angles to the beds. The layers of rock may then have undergone more movement, more disruption, cracking and folding creating new lines of weakness. These, in turn, were injected with crystalline material which slowly cooled over thousands of years. Finally the action of the ocean took its turn to find new opportunities to sculpt the rocks to create the forms we now see.

For me, this describes the ideal creative process, which in a way I attempt to mimic in my working practices. Clearly it is impossible to harness the powers of nature but it is the idea that what we see here is 'consequential' that interests me. That is, whatever remains visible to us is as a result of an action - a process. The results of the earths powers are not contrived, there was no grand design at the outset, no plan. This, I strive for in my creative output. Process is all, barely in control and seeking to make interventions only where invitations appear.